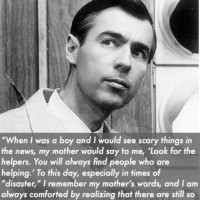

Fred Rogers had a television show when I was a child that ran for over three decades. It was a safe haven for young hearts… slow and peaceful it was, with an invitation to imaginal worlds and a knowing of one’s own self worth.

Fred Rogers had a television show when I was a child that ran for over three decades. It was a safe haven for young hearts… slow and peaceful it was, with an invitation to imaginal worlds and a knowing of one’s own self worth.

The man had a way about him so you just knew he was well and truly a teacher of Love.

We need more Mister Rogers in this world, and no more Mr. Trumps.

Anyway, I see that Donald Trump is doing us all a huge service by showing with inescapable clarity how diseased our society has become. We can’t move to resolve that situation until it starts freaking us out. I do believe we have arrived.

April 13, 2016

By Caitlin Dickson

httpss://www.yahoo.com/news/campaign-rhetoric-inspires-chaos-anxiety-in-220831135.html

A Catholic bishop in Indiana denounced the Andrean High School students who waved a picture of Donald Trump and shouted “Build a wall!” at their opponents from a largely Hispanic school in nearby Hammond, Feb. 26, 2016. (Photo: Jonathan Miano/The Times via AP)

Barbie Garayua Tudryn first noticed that the presidential election was having an unusual effect on the students at Frank Porter Graham Elementary back in September.

Tudryn, who has been the guidance counselor at the English-Spanish bilingual school in Chapel Hill, N.C., since 2008, usually kicks off each school year with a lesson on diversity.

“The kids were different this year,” Tudryn told Yahoo News. “As soon as I brought up the topic of how we’re all different and how our school represents so many pieces of the puzzle, the kids started talking about their own skin colors. From there they were saying, “If Trump wins, all the brown people will be taken out.”

As the primaries have progressed, Tudryn said, those kinds of ideas have only become more ingrained in the students at Frank Porter Graham — 55 percent of whom are Latino. Tudryn said she’s seen kindergarteners shiver with fear upon hearing the word “Trump,” and watched third-grade classrooms devolve into utter chaos at the mere mention of the election.

While previous presidential elections have typically been incorporated into the third-, fourth- and fifth-grade civics lessons, now, Tudryn said, “The teachers don’t even want to go there because they know it’s going to turn into a major mess.”

“They’re afraid of losing control or getting an email from a parent or getting accused of talking about politics in class,” she continued. “It’s unfortunate, it’s part of our job we need to teach this, but the [candidates’] rhetoric is not making it possible.”

Tudryn is one of thousands of educators from around the country who are concerned about the negative impact the current presidential primary appears to be having on their students, according to a new report from the nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance project, which aims to promote diversity and acceptance in schools.

Disturbed by recent reports of Indiana high schoolers chanting “Build a wall!” during a basketball game against a largely Hispanic team, or third graders in Virginia warning their “immigrant” classmates that they’ll be sent home when Trump is elected, researchers at the Teaching Tolerance project set out to learn more about how this historically unconventional campaign is affecting America’s youngest citizens.

“We realized there’s no real source of data,” Maureen Costello, the project’s director, told Yahoo News. “Rather than speculate about it, we decided to ask our wealth of teachers.”

Costello and her team crafted a survey and distributed it to their large network of K-12 educators via their email newsletter as well as the Teaching Tolerance website. More than 2,000 teachers from every state in the country responded, and while Costello said she wasn’t exactly surprised by the responses, “on the other hand, they shocked me.”

According to the report released Wednesday, more than two-thirds of the teachers surveyed said that many of their students — particularly those who are either Muslim, Latino, or first-generation Americans — have expressed “fear that they or their parents will be deported — or worse — after the election.”

While the report finds that “children of color, in particular, are being deeply traumatized,” Costello notes that other students appear to be “emboldened by the divisive, often juvenile rhetoric” heard on the campaign trail. More than a third of teachers reported hearing an increase in anti-Muslim or anti-immigrant comments, and more than half say their students have become increasingly unable to engage in civil political discourse.

Worried about maintaining control over their classrooms, more than 40 percent of the teachers surveyed said they are reluctant to discuss the election in class.

This, Costello said, is particularly concerning. Not only does such anxiety and classroom chaos prevent kids from learning, she explained, but by avoiding the conversation, teachers are actually depriving their students of one of the key lessons used to “grow kids into citizens in this country.”

“They’re not learning what it means to self-govern, and that really bothers us,” she said.

Though the survey did not refer to any specific candidates by name, comments from the teachers surveyed overwhelmingly cited Donald Trump more than any other presidential candidate.

That’s certainly the case at Frank Porter Graham Elementary, where Tudryn said, “all you hear is Trump this, Trump that.”

Tudryn suggested that may be due in part to the fact that the Republican frontrunner’s last name “is kind of catchy for little kids.” But she also knows that many of the children whose parents speak Spanish at home are exposed to Telemundo and Univision, TV channels whose Spanish-language election coverage is often particularly critical of Trump.

Despite the fact that approximately 90 percent of the Latino students at her school are documented, Tudryn said that a lot of their fear surrounding the election stems from a lack of understanding about what that means. A big part of quelling those students’ concerns involves helping them understand that their citizenship is no different from that of their fellow students.

Another part of that effort involves educating students — and their parents — on how the U.S. electoral process works, something Tudryn has found especially crucial for the children of immigrants from countries with volatile political systems like Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras.

“In their parents’ minds, anything can happen,” Tudryn said. “But if your kid is a citizen and you are not a citizen, what you communicate to your child is critical to them having citizen ownership and feeling like a part of the United States.”

Latino children are hardly the only ones taking Trump’s inflammatory words to heart. Teachers who responded to the survey reported observing similar anxieties among their Muslim and African-American students, reinforcing the fear first outlined by Washington Post columnist Petula Dvorak last month that “it may take an entire generation to recover from the hateful rhetoric [Trump has] aimed at immigrants, Muslims and Black Lives Matter protesters.”

Trump, for his part, has emphatically dismissed the suggestion that he is to blame for young kids repeating language heard at his campaign rallies to taunt their Muslim or Latino classmates. But just last week in Wisconsin, several black and Latina high school soccer players were reportedly driven to walk off the field at a game by chants of “Donald Trump, build that wall!” from white fans of the opposing team.

Tudryn knows for sure that if Donald Trump becomes the Republican nominee “we’re not going to have any option but to address this,” but she is comforted by the fact that she works at a bilingual school where both students and their parents “can come in and feel supported.”

“I am so worried about the schools that don’t have any staff that speak Spanish or don’t understand what it’s like to be an immigrant in this country,” she said. “I cannot even begin to think how isolating it must feel to be in those schools with no Latino staff. That’s scary.”