November 20, 2021

November 20, 2021

Yesterday, I witnessed an act of kindness delivered to a homeless person sitting on a fireplug at an intersection in the middle of nowhere.

Yesterday, I witnessed an act of kindness delivered to a homeless person sitting on a fireplug at an intersection in the middle of nowhere.

From one of the industrial buildings nearby, an employee brought a paper plate covered with foil to the woman rocking side to side on the bright yellow fireplug. I glimpsed her gap-toothed smile in my sideview mirror as she accepted the plate, then drove on my way, moved almost to tears.

Today, I gave Jesse the troubadour a long unafraid hug in front of the Goleta Trader Joe’s. He was in his usual spot in front of the store, but, he said, he’d have to leave, as one of the security guards just told him to move along.

“This is what I miss the most,“ he murmured into the hug, and I felt my heart simultaneously contract with pity and expand with something its opposite.

Tears and beauty in the same breath. How very like Life that is.

*****

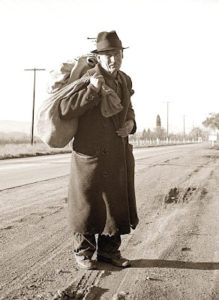

The homeless vagabond is both archetype and reality. I haven’t paid a great deal of attention to either over the years, at least until recently.

The homeless vagabond is both archetype and reality. I haven’t paid a great deal of attention to either over the years, at least until recently.

There is something quintessentially mournful about these humans who have ended up living on the street. Growing up east of San Francisco in the quiet suburb of Lafayette, I only came in contact with people in similarly comfortable circumstances. All I knew of homeless people was that they congregated by Lake Merritt in Oakland, and all over downtown San Francisco.

When my mother would occasionally drive us over the Bay Bridge to the city for shopping and luncheon at the iconic City of Paris, we would inevitably encounter shuffling derelicts clutching bottles in paper bags.

My mother would grip my hand more tightly and hurry past, high heels clacking on the pavement. I’m not sure if she actually said, don’t pay them any attention, but the message was still there.

I don’t fault her. She was being protective. That protective attitude has been with me my entire life.

Don’t stop, don’t talk, pretend they’re not there. Feel sorry for them but don’t give them money, they’ll just go spend it on booze.

*****

Somewhere in my older adulthood, that closed mental loop has begun to dissolve. My well-established fear of street people has diminished. Not that I’m foolish about it; I wouldn’t put myself in harm’s way. But that automatic clutch of caution and aversion no longer grips me the moment I see a panhandler. I am more able to look at the person as an individual, not as a generic source of potential danger.

Somewhere in my older adulthood, that closed mental loop has begun to dissolve. My well-established fear of street people has diminished. Not that I’m foolish about it; I wouldn’t put myself in harm’s way. But that automatic clutch of caution and aversion no longer grips me the moment I see a panhandler. I am more able to look at the person as an individual, not as a generic source of potential danger.

The most curious thing about this is that I hadn’t even realized my attitude was shifting. What I have noticed has been almost entirely in relation to Jesse the troubadour.

He’s been panhandling, guitar in hand, for years in front of the Goleta Trader Joe’s. I used to walk quickly past him, not making eye contact.

Then one time I looked at him, and said hello, and felt the sunshine of his smile.

Just before the pandemic lockdown started, I was at the point of chatting and dropping a bit of coin into his guitar case. Then Covid hit and he journeyed east to be with family.

When he finally returned a couple of months ago, I was blindsided by the joy I felt at seeing him.

From uneasiness and discomfort to joy. If that’s not a miracle, I don’t know what is.

*****

A plate of hot food on a cool day, given from no apparent motive but kindness.

A plate of hot food on a cool day, given from no apparent motive but kindness.

A long hug in front of a busy grocery store in a suburban strip mall.

All I’m really sure of is that all of us in these tableaux are equally beloved of God. And that the giving and the receiving are inextricably entwined.

Who can say which of us receives the most? Which of us is most in need?

I feel the stony corners of my heart gradually being chipped away. One gap-toothed smile, one hug, at a time.

What’s left feels pure as gold, and shines as bright as God.