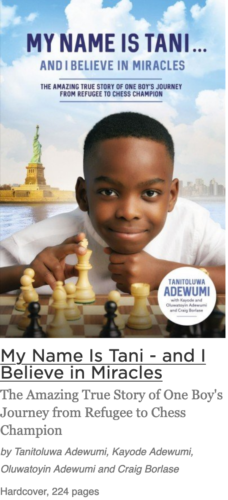

Nine-year-old Tani Adewumi was hoping to defend his title this weekend at the New York State Scholastic Chess Championship. The tournament was canceled due to Coronavirus. When Tani won the primary school division in 2019, he was living with his family in a homeless shelter. HarperCollins

Long and heart-warming. . .

By Elizabeth Blair, NPR, March 12, 2020

The story of how 9-year-old Tani Adewumi became a chess prodigy begins nearly five years ago, in a print shop in Abuja, Nigeria. Tani’s father, Kayode Adewumi, owned the shop, and printed textbooks, manuals, flyers – whatever his clients wanted.

But one day in December 2015, four men came in with an order for 25,000 posters. Adewumi didn’t know it at the time, but they were members of the terror network Boko Haram. Later that evening, Adewumi looked at the flash drive they’d given him, and found their poster said in Arabic: “Kill all Christians. Death to western education.”

Adewumi is Christian. When the men came back to pick up their order, he pretended the printing machines were broken and suggested they go elsewhere. The men didn’t believe him, so Adewumi pretended to take a call on his cellphone and slipped out the back door.

Not long after, Adewumi was away on business, and men showed up at his house. When his wife Oluwatoyin opened the door, they burst in, threatened her at gunpoint, and demanded to know where her husband was.

More than four years later, sitting on a couch in a Manhattan apartment where the Adewumis have lived for the past year, Oluwatoyin shudders at the memory.

“I put my head down. I don’t want to look at anybody’s face because, we hear it in the movies, ‘Can you recognize my face?’ So I don’t want to recognize anybody’s face,” she remembers.

Having been raised Muslim, she spoke a few words to them in Arabic, including the word “Please.” They asked her if she was Muslim. She said “yes,” and eventually they left.

The Adewumis suspect the men noticed the cross hanging on a wall in the print shop.

Tani, center, shares a laugh with his family — big brother Austin, his mom Oluwatoyin and his dad Kayode. The Adewumis came to the U.S. from Nigeria in June 2017. HarperCollins

Tani and his older brother Austin slept through it all. “We were snoring!” Tani, now 9, chimes in from across the room. The Adewumis moved to another part of Nigeria but Kayode and Oluwatoyin continued to believe their lives were in danger. In June 2017, they left the country on tourist visas.

Eventually they made their way to Queens where they met Nigerian Pastor Philip Falayi who says he’s helped dozens of families like the Adewumis. “They come to me, I help them, they move on. They come to me, I help them, they move on,” he says.

Pastor Philip (as congregants know him) let the Adewumis stay in his basement and connected them with New York’s Department of Homeless Services. The family was given temporary housing in a shelter located above a hotel in Manhattan: Oluwatoyin and Kayode on one floor; 7-year-old Tani and his 14-year-old brother Austin on another.

Tani didn’t like having to go to another floor just to see his mom and dad. His parents, however, were relieved. “We thank God we were able to find somewhere to put our heads,” says Oluwatoyin.

Tani and his brother enrolled in a nearby public school that had an active chess club. Tani wanted to join. When his mother told the coaches they were living in a shelter and couldn’t pay the $330 fee, they waived it.

Tani’s coach, Shawn Martinez, says the 9-year-old isn’t afraid of anything on the board — and “that’s what it takes to beat the best of the best,” he says. Oluwatoyin Adewumi

Coach Shawn Martinez says Tani’s potential was clear from the outset. “He has an incredible memory and he’s very interested in what he’s learning,” Martinez says.

Tani is obsessed with chess — reading books about it, studying famous masters and playing chess games online. Even his coaches like playing him. The day I visit his apartment, Tani sits across from Coach Shawn, concentrating, his hands gripping his head. Martinez is a chess master, but that doesn’t faze Tani. “I think you’re getting into trouble,” he tells his coach.

Tani wasn’t a shoo-in for first place in the primary division at the 2019 New York State Scholastic Championship. He’d only been playing for a year and admits, after winning five games in a row, he nearly lost the final, deciding game of the tournament. “I was winning but then I blundered,” he says. It was a blunder that Tani says could’ve lost him the game. But before his opponent noticed it, “I offered a draw and he took it,” he says.

When Tani won that tournament, his coaches — eager to help the family find a way out of the shelter — spread word to the media about this young chess prodigy whose family was homeless. New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof wrote an op-ed with the headline “This 8 Year Old Chess Champion Will Make You Smile.”

Coach Shawn Martinez says chess is a game that “honors intelligence, character and how much you invest in it.” HarperCollins

“Almost as soon as it went online, there was a huge response,” says Kristof. “I was kind of taken aback by it. Fortunately, the chess coaches were way ahead of me and they had set up a GoFundMe.”

The New York Times column turned Tani’s win into a global story. Kayode Adewumi says they were inundated with interview requests from other countries. “Everything just blew up,” Adewumi recalls. “I now strongly believe that this is God that wants to bless us.”

The GoFundMe page raised more than $250,000 within 10 days. An anonymous donor offered to pay their rent on an apartment for one year. Trevor Noah bought the movie rights to Tani’s story and the family co-wrote a book with bestselling author Craig Borlase. My Name Is Tani . . . and I Believe in Miracles will be published in April.

“I mean it’s absolutely a beautiful story,” says Martinez. As a coach, he’s seen chess help a lot of young people through adversity – but you have to work hard at it. Chess “honors intelligence, character and how much you invest in it,” Martinez says.

He says he considers Tani “between a lion and a tiger.”

“He’s not scared of anything on that board and that’s what it takes to beat the best of the best,” Martinez explains.

Tani’s mother is amazed at how her son’s passion for chess has transformed their lives. Oluwatoyin Adewumi doesn’t play herself, but she remembers something Coach Shawn once said about strategy: “When you put pawns together, there’s no stopping them.”

Adewumi says the teachers, pastors and fellow immigrants who came together to help her family might be seen as pawns.

“You might see them looking so small, but they are very powerful,” she says.

With the proceeds from the GoFundMe site the Adewumis created a foundation in Tani’s name that helps children “achieve excellence in learning the game of chess.”

In the meantime, Tani’s chess rating keeps climbing, putting him ever closer to his goal of becoming a master.