Canadians are protesting, and it’s about a lot more than a pipeline, as the post below says.

Canadians are protesting, and it’s about a lot more than a pipeline, as the post below says.

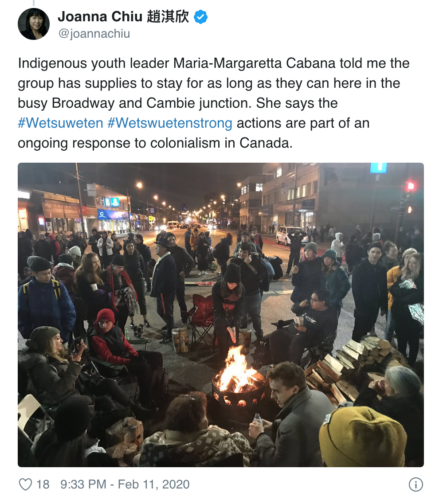

A fire is lit on the legislature steps in Victoria, BC, the Granville Street Bridge in Vancouver was shut down, the intersection at Cambie and Broadway was blocked, and a sacred fire lit there, as well.

Photo: Dan Toulgoet

Broadview Wet’suwet’en acts of solidarity by youth give me courage

Vice Day One and Day Two: RCMP Are Raiding Wet’suwet’en Land Defender Camps

HuffPost: Wet’suwet’en Coastal GasLink Pipeline Dispute

It’s about a lot more than a pipeline.

By Melanie Woods, February 12, 2020, HuffPost

People on Wet’suwet’en land are speaking out, and people across the country are listening.

The dispute between Indigenous hereditary chiefs and RCMP enforcing an injunction to build the Coastal GasLink pipeline through their land has exploded into a national headline, as protesters and land defenders occupy ports, rail lines and intersections across Canada to draw attention not only to the pipeline, but also to Indigenous land rights on the whole.

From Halifax to Victoria, chants of “Wet’suwet’en strong” are echoing out. Hundreds of protesters successfully occupied the B.C. legislature Tuesday, delaying the speech from the throne.

CN rail could potentially close rail lines as a result of protests across Canada.

But what is the difference between Unist’ot’en and Wet’suwet’en?

How about elected band councils and hereditary chiefs?

What do all those kilometre marks mean when you hear them referred to in the media?

It’s important to know what you’re talking about when you’re talking about the dispute in northern B.C., so here’s a handy guide to all the terms and names you might hear surrounding it.

For the latest updates on the evolving story and nationwide protests, click here.

Wet’suwet’en:

The Wet’suwet’en are a First Nations people residing in northern British Columbia. The nation is composed of five clans: the Gilseyhu (Big Frog), Laksilyu (Small Frog), Gitdumden (Wolf/Bear), Laksamshu (Fireweed) and Tsayu (Beaver). Wet’suwet’en means “People of the Wa Dzun Kwuh River (Bulkley River),” referring to the river that snakes through Wet’suwet’en land.

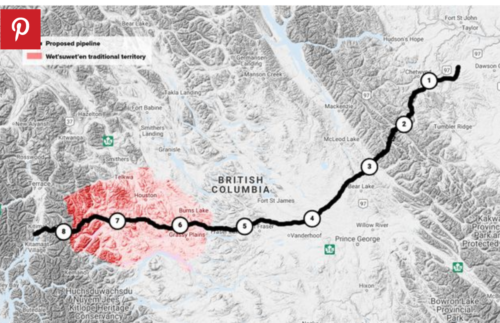

Wet’suwet’en territory:

The traditional lands of the Wet’suwet’en, an area covering hundreds of square kilometres in central northwestern B.C.

Planned construction phases along the proposed pipeline route and how it intersections with Wet’suwet’en

Erica Rae Chong/HuffPost Canada

Unist’ot’en:

Refers to the encampment set up at kilometre 66. It is the most established of the camps, with permanent dwellings and a healing lodge. Unist’ot’en was actually established in 2009 in anticipation of pipeline construction efforts on Wet’suwet’en land. It acts as a checkpoint of sorts, and people are not permitted to pass through without permission from Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs. It also contains a key bridge, which Coastal GasLink says is essential for crews to access the pipeline construction area. You might be familiar with the bridge from images of a barrier literally with the word “reconciliation” being torn down by RCMP on Monday.

Gidimt’en:

Another camp along the route, named for the Wolf/Bear clan.

Kilometre markers:

You’ll often hear locations along the Morice West Forest Service Road described by number of kilometres — the Unist’ot’en camp, for example, is located at kilometre 66 west. This number refers to the kilometre marker on the road indicating how far off of Highway 16 — a stretch of which is often known as the Highway of Tears — the camp is. The first Wet’suwet’en camp is located at kilometre 33.

Exclusion zone:

This phrase is used in reference to an ever-shifting area set up by the RCMP where they are giving people within the opportunity to leave or face arrest. This is the area under the court injunction. It also happens to encompass a lot of Wet’suwet’en land. When you read about people being arrested, it’s likely in the exclusion zone. The exclusion zone has also been called into question in its legality.

“There is absolutely no legal precedent nor established legal authority for such an overbroad policing power associated with the enforcement of an injunction,” reads a letter from the B.C. Civil Liberties Association to RCMP commissioner Brenda Lucki.

“The arbitrary RCMP exclusion zone and overbroad access restrictions are completely unjustified and unlawful, and constitute a serious violation of Indigenous rights.”

For more on those rights, see Delgamuukw v British Columbia below.

Injunction:

The injunction we’re talking about here is one issued by the B.C. Supreme Court on Dec. 31, which granted Coastal GasLink an expanded injunction against the Wet’suwet’en Nation members blocking access to the project. On Thursday, RCMP began enforcing that injunction and arresting people on the route. Dozens of protesters and land defenders have been forcibly removed from the territory contained within the exclusion zone as a result of the injunction.

Coastal GasLink:

The company behind the pipeline. The $6.6-billion, 670-kilometre pipeline would carry natural gas across northern B.C. According to Coastal GasLink’s website, the company consulted with First Nations, government, landowners and stakeholders when deciding the pipeline’s route. The pipeline is set to terminate at Kitimat, not far from the Unist’ot’en camp.

Hereditary Chief Ronnie West from the Lake Babine First Nation, sings and beats a drum during a solidarity…

Darryl Dyck/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Elected band council:

Coastal GasLink says it has signed agreements with the elected council of all 20 First Nations along the route, including the Wet’suwet’en. Now this is where it gets tricky. Elected band councils are very different from hereditary chiefs (see below). Band councils were established by the Indian Act to have authority over reserve lands. So while the band councils may agree to something, that doesn’t mean they have the permission of traditional authority structures.

Hereditary chief:

A council of 13 hereditary chiefs governs the traditional structure of the Wet’suwet’en predating colonialism and represents the five clans. And it’s the hereditary chiefs who oppose the pipeline and the hereditary chief whom thousands of protesters across the country are standing in solidarity with. They say they’ve never agreed for the pipeline to pass through their territory or to hand over land for its construction.

Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs Rob Alfred, John Ridsdale and Antoinette Austin take part in a rally in…

Jason Franson/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Unceded land:

Wet’suwet’en land is unceded, meaning it was never signed over on paper to Canada through a treaty. This is important, because the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs assert a legal right to the land and a right to decide who uses it for what. Of course, it’s important to note than even if a treaty was signed between Canada and existing Indigenous peoples, that doesn’t mean the land was “given up” or given away. There’s a lot of complexity behind the legacy of the treaty system.

Delgamuukw v British Columbia:

This landmark court case in the Supreme Court of Canada from 1997 established Indigenous rights to traditional territories and was the first comprehensive account of Aboriginal title — a common law doctrine that essentially says Indigenous peoples’ rights persist after settler colonialism — in Canada.

While the case upheld Indigenous peoples’ claims to unceded lands, it didn’t resolve the specific question of title for the Wet’suwet’en, and subsequent court cases were never launched so things are still very much up in the air in a legal sense.

But a big part of that title and claim to land defined by the Supreme Court comes from continuous occupation — a hypocrisy many are pointing out as Wet’suwet’en people occupying their land to prove ownership are being forced off it by the injunction.

I invoke Wakanataka, White Buffalo Calf Woman,

Chief Sitting Bull, Chief Cochise, Chief Red Cloud,

Chief White Cloud, Chief Joseph, Chief Geronimo,

Sanat Kumara, St. Germaine, the Mighty Ones, and

all the Universal Laws, the Divine Blessings, Virtues,

Qualities, the Dimensional Growth Patterns for Peace,

Love, Joy, elimination of bigotry, hatred, control, greed,

the insidious unconscious ways not of love within/without.