Margaret Drescher hugs Ulnooweg’s Chris Googol as her husband, Jim, looks on. (Photo: Rove Productions)

These settlers are going beyond orange shirts and land acknowledgments. Land Back is an Indigenous-led movement to reclaim traditional lands for Indigenous stewardship.

By Sarah Treleaven, Broadview,

Last June, Margaret Drescher prepared herself to finally pass along Windhorse Farm, a beloved retreat deep in the forest about an hour-and-a-half drive west of Halifax.

All the official documents had been signed months before — the cerebral part of the transaction, she notes — but the June event wasn’t about paperwork or ownership. It was a spiritual return of the property.

Rejecting the idea of ownership, Drescher and her husband, Jim, had decided to turn over the roughly 80 hectares of old-growth forest to the Ulnooweg Education Centre, an Indigenous-led charitable organization that works with communities across Atlantic Canada.

The Dreschers transferred the property for an amount (below market value) that would allow them to meet their needs, believing that the land belonged back in Indigenous hands. (They still live in their home on the neighbouring peninsula.)

That June day was full of Elders and children, with smudging and jingle dances and drumming. “There was just heart, there was humour,” says Drescher. “It was completely beautiful. Jim and I woke up the next morning, looked at each other and went, ‘Okay, things are different.’”

I first heard about the transfer of Windhorse Farm a year or so ago, and it followed another story that I read with curiosity: in July 2021, an Indigenous woman in British Columbia turned to social media to recruit settler Canadians to offer up their holiday homes for free vacations for “exhausted Indigenous kin.”

Jacqueline Jennings tweeted, “Because of forced displacement, broken treaties, legislated poverty and land theft and the Indian Act, many Indigenous folks don’t have access to the intergenerational financial wealth (have other kinds) and credit to have a recreational property, 2nd or 3rd home.”

Pitching it as “soul cleansing restitution,” Jennings noted that “you won’t even have to give Land Back forever…just a couple of weeks by your pool/beach/lake/mountain.”

Although I couldn’t find evidence that any homes changed hands, and Jennings didn’t respond to interview requests, her point was clear: Canadians need to make reconciliation more personal.

Most of Canada’s reconciliation process has been framed as an institutional undertaking — governments and churches apologizing and paying settlements — while individual Canadians have largely been tasked with occasionally wearing an orange shirt and putting a land acknowledgment in their email signature.

But some Indigenous scholars and leaders have cautioned against purely symbolic gestures and asked individuals to dig deeper.

So what does it look like to turn institutional atonement into personal atonement, to commit individual resources to the effort to right horrific historic wrongs?

What are individual settlers’ opportunities and responsibilities for reconciliation with Indigenous peoples?

For an increasing number of non-Indigenous Canadians, reconciliation isn’t just an arms-length commitment; it’s a personal call to action.

Margaret and Jim Drescher grew up in the United States — she’s from California, and he’s from Wisconsin — but they found their way to Nova Scotia more than 40 years ago.

In 1990, living in Halifax with their two young children, the couple were juggling a few small businesses when their financial struggles reached a breaking point.

Their house was being foreclosed on, and their car was about to be repossessed.

“We were selling our children’s toys to buy food,” says Drescher, who is slim with shoulder-length grey hair and has a calm and generous demeanour.

A colleague, familiar with their interest in conservation, advised them to check out a property for sale in the middle of the woods.

Windhorse Farm was previously owned by Caroll and Marion Wentzell.

Deforestation was accelerating across the province, and Drescher says most of the prospective buyers seemed to be loggers and timber brokers looking to clear-cut the property.

When the Dreschers went to view the farm, they were invited into the kitchen.

Carroll and Marion had been married for 57 years and were then in their 80s.

Carroll stayed quiet for the entire visit, save for one question: What do you want to do with the forest?

“We said — it makes me emotional just to say it — ‘We want to do what you did,’” recalls Drescher.

That marked the turning point in the conversation.

A friend lent them the $25,000 down payment.

After living in the city for so long, they found the move to Windhorse Farm an adjustment. But Drescher had always loved gardening, and her husband has a master’s degree in ecology.

From the very beginning, the land seemed to call to her.

The first time she put her shovel into the vegetable garden, what she heard was clear. “I thought, this land belongs to the Mi’kmaq,” she says. “This land does not belong to me.”

But it would take decades for the couple to figure out how to facilitate that return

In a letter posted to the Windhorse website in the lead-up to the property transfer, the Dreschers describe themselves as “mere placeholders waiting for this auspicious ‘land-back’ event to occur.”

Land Back is an Indigenous-led movement to reclaim traditional lands for Indigenous stewardship.

In a Red Paper, the Yellowhead Institute’s executive director Hayden King and former research director Shiri Pasternak write that “there is a stubborn insistence by Canada, the provinces and territories, that they own the land.

For many Indigenous communities, this is a deep violation of their consent to determine what happens on unsurrendered lands, but also a violation of the broader assertion that they have jurisdiction over those lands.”

These ideas, honouring Indigenous people’s rights to the land and helping to ameliorate land alienation, inspired the Treaty Land Sharing Network (TLSN) in Saskatchewan.

The organization connects farmers, ranchers and other landholders with Indigenous land users looking to “practice their way of life.”

Valerie Zink, a settler from a farming family, and Philip Brass, a Saulteaux and Cree artist, hunter and land-based educator from the Peepeekisis Cree Nation, launched the TLSN in 2021.

It now includes 39 locations across more than 8,300 hectares in Treaty 4 and Treaty 6 territories.

Nettie Wiebe first thought about sharing her organic farm with her Indigenous neighbours a decade or so ago.

She lives about 70 kilometres from Saskatoon and grows lentils, oats and wheat, along with tending a small herd of beef cattle.

The initial plan — to create space for a sweat lodge — didn’t come to fruition.

But in 2016, after 22-year-old Colten Boushie was killed by a Saskatchewan man after driving onto his farm, Wiebe felt a real jolt.

“The response to that, in rural Saskatchewan, was for me, personally, just totally unnerving.”

She was struck by “how racist, how disrespectful, how hateful a lot of the reaction [was] from farmers.”

When she heard of the TLSN, Wiebe was immediately supportive.

“It spoke to what we hoped for, which was that there would be reconciliation and respectful, peaceful restoration of relationships between us, the settler class, and the Indigenous peoples who were here thousands of years before us,” she says.

She posted signs from the TLSN that say “Indigenous Land Users Welcome” and has already fielded interest from some Indigenous people looking to hunt on the property.

In June, she hosted an event that brought together an Elder, TLSN members and other participants to learn about the land, reconciliation and the honouring of treaties. Colten Boushie’s mother attended.

Tom Harrison has a herd of about 250 grass-fed cattle on around 1,600 hectares in south-central Saskatchewan.

When I spoke with him, he was driving a truck full of cows to Manitoba for slaughter. Harrison has long been interested in conservation, setting aside land for perennial ground cover and creating habitats for wildlife.

More than two decades ago, he worked with the Saskatchewan Indian Agriculture Program and File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council, supporting farmers on reserves.

That work led him to learn more about the suppression of Indigenous peoples through the reserve system and the seizure of land. Eventually, Harrison spoke to his wife about putting up a sign to note that they were treaty friendly.

They weren’t sure how they’d approach it. Then, while Harrison’s wife was scrolling through social media, she found the TLSN. They have since had several hunters visit.

Harrison’s involvement with the network has created opportunities for dialogue.

One visitor told him about his father’s experience in a residential school.

A man gave him fresh-caught fish.

Another person expressed frustration that so much land is inaccessible, marked by no-trespassing and no-hunting signs.

“The sign that the Treaty Land Sharing Network puts up reflects a mindset of ‘You’re welcome to come out here,’” says Harrison.

At Windhorse, the years went by and the Dreschers’ vision for the property grew.

They started permaculture gardens in the 1990s and built little cabins in the woods to host gardening interns and eco-forestry students.

In 2002, they built Juniper Lodge to host retreats.

Margaret Drescher says she wanted the lodge to be “a place where people could come, feel safe, feel cared for, and then be able to go out onto the land.”

The property also includes a farmhouse built in 1840, a barn and a woodshop, as well as about 22 kilometres of walking trails.

In 2016, the Dreschers started to think more concretely about how to transition the land.

They had managed the property for over 25 years, Margaret had cancer and they both realized they were getting old. But they wanted to entrust the property to caretakers with the same interest in preserving the forest, land and water.

Richard Bridge, a settler lawyer, was then on the board of directors for the Windhorse Education Foundation, the charitable organization that manages the forest on the property.

He also serves as strategic and legal counsel for Ulnooweg, a 37-year-old not-for-profit that provides financial and community development services to Indigenous businesses and communities in Atlantic Canada.

He offered to resign from the Windhorse board to facilitate the transition to Ulnooweg.

Those conversations would take four years.

Drescher is still moved by the initial discussion. “Their first question to us was, ‘Well, what do you see? What do you need?’” she recalls. “And the natural response to that is, ‘Well, what do you need?’”

They went from there.

Reconciliation projects aren’t simply about land, of course.

Rev. Nobuko Iwai, minister at Grosvenor Park United Church in Saskatoon, felt called to read the final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), so she gathered a small group of people from different faiths to collectively read and discuss the nearly 1,100-page report.

“We didn’t want to burden people who are constantly being asked to tell their story, and we felt as if we needed to do our own work,” says Iwai.

The 2019 report was eye-opening and revealed ongoing injustices that the group hadn’t been aware of.

“For a lot of us, the birth alert was a really big thing,” she says, referring to the practice in which a child welfare agency notifies hospital staff about concerns regarding a baby’s well-being, from family poverty to a parent’s history in the child welfare system.

“I just couldn’t believe that that was happening.”

Birth alerts may result in the apprehension of infants and children by child welfare.

“Indigenous children were taken from their families and communities in so many ways,” she says. Following their reading, the group committed to donating to Iskwewuk E-wichiwitochik (Women Walking Together), an organization that works on the issue of MMIWG.

In downtown Sydney on Cape Breton Island, N.S., a mural painted in 2019 in a collaboration between an Indigenous and settler artist has become a focal point for the community.

It depicts many things, including a tree with hanging red dresses, symbolizing missing and murdered Indigenous people.

There’s a woman holding a smudge bowl, representing the healing of generational trauma.

It features the seven sacred teachings in Mi’kmaw, English and French. And it depicts Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in dialogue — which is how the piece was conceived and executed.

The process took more than six weeks, as Mi’kmaw artist Loretta Gould and settler artist Peter Steele worked through challenges.

“Loretta and I did go back and forth and back and forth,” says Steele. They would paint for a bit, then walk across the street and chat about the mural.

The decision to add the tree with the red dresses was made after the work had already begun. “If we’re going to get into reconciliation, it has to do with more than just the residential school system,” he says. “It has to include literally every aspect of how we have treated each other.”

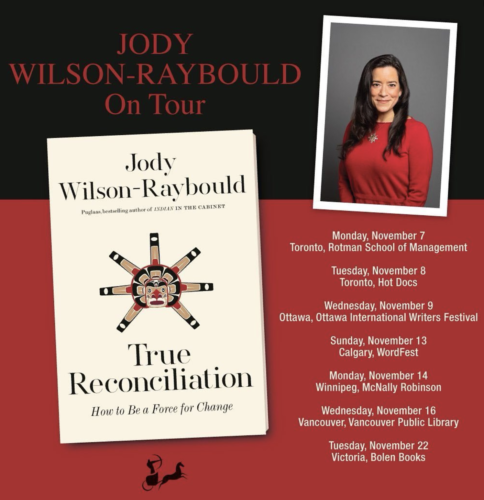

Jody Wilson-Raybould Publishing New Book,

True Reconciliation, to be Released November 2022

CBC Books

https://www.cbc.ca/books/jody-wilson-raybould-publishing-new-book-true-reconciliation-to-be-released-in-november-2022-1.6411717

Jody Wilson-Raybould, the bestselling author of Indian in the Cabinet and From Where I Stand and a former justice minister for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal parliament, is publishing her 3rd book.

True Reconciliation: How to Be a Force for Change will be released on Nov. 8, 2022. It will be published in Canada by McClelland & Stewart.

Drawing on Wilson-Raybould’s extensive career, True Reconciliation: How to Be a Force for Change is a guide that seeks to improve relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples at all levels of society.

“From coast-to-coast-to-coast — in various ways and more than ever before — Canadians are wanting to play their part in moving towards true reconciliation with Indigenous peoples,” Wilson-Raybould said in a statement.

“This book is about helping change a conversation that has become unnecessarily complicated. We have the solutions, and we know what needs to be done.”

Wilson-Raybould’s most recent book, Indian in the Cabinet, is shortlisted for this year’s Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing. The political memoir was also a finalist for the 2021 Balsillie Prize for best Canadian public policy book.