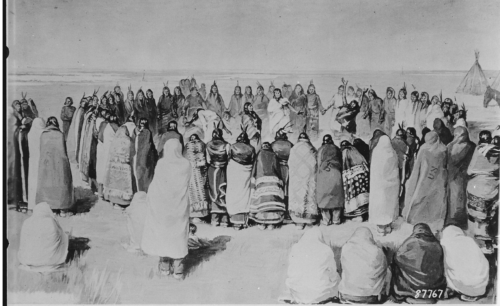

Illustration of an Arapaho Ghost Dance, based on photographs from the early 1890s. (Image courtesy of the U.S. National Archives)

The Indigenous Ghost Dance is one of ‘renewal and restoration’

But one theologian says we shouldn’t confuse a vision central to the Ghost Dance faith with western end-times imagery

By Damian Costello, Broadview, June 7, 2022

https://broadview.org/wanikiya-lives-on/

The story goes that during a solar eclipse on Jan. 1, 1889, Wovoka, the Paiute mystic from Smith Valley, Nev., had a dream where he was taken up to heaven. There, he met an Indigenous Christ and saw the new heaven and new earth promised in the Book of Revelations. In this vision, the dead would rise and the land would heal of wounds inflicted by newcomers. All one needed to do was live in peace, work hard, go to church and dance.

Wovoka’s prophecy led to the Ghost Dance movement, which exploded across the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains in the years that followed. On reservations, groups danced all day in a circle around a tree symbol singing the songs gifted to Wovoka. Abstaining from food and water, many fell down and saw their dead relatives — and the world to come.

“The Ghost Dance faith is the faith of many Indigenous Christians today, but we shouldn’t get confused with the western end-times scenarios of destruction and annihilation,” says Mi’kmaq theologian Terry LeBlanc.

Though I am not Indigenous, the Ghost Dance spoke to me about the “end times” with an immediacy I didn’t find in my Christian church circles. For Ghost Dancers, Christ’s resurrection was real and transformed all of Creation.

The Indigenous Christ visited his children through visions. The most famous recipient of these visions was Nicholas Black Elk, the Lakota holy man who later became a candidate for sainthood in the Roman Catholic Church. While dancing in 1890, Black Elk flew over the Promised Land and saw a man with an eagle feather in his long hair, with pierced feet and hands, surrounded by light. “My life is such that all earthly beings that grow belong to me,” the man told Black Elk. “My father has said this. You must say this.”

The Lakota called this figure Waníkiya: “He Who Makes Live.”

Colonial authorities, however, saw the resurrected Indigenous Christ and his Ghost Dance followers as rebels. Hysteria culminated in military buildup and tragedy: on Dec. 29, 1890, the United States Army massacred more than 250 Lakota near Wounded Knee Creek, S.D.

Still, the Indigenous Christ lived on. In fact, even before Wounded Knee, large numbers of Ghost Dancers entered “mainstream” denominations. Followers entered churches, too. Black Elk, for instance, became a prominent Catholic lay leader at St. Agnes in Manderson, S.D. In July 1909, he wrote a letter in the Lakota Catholic newspaper, urging, “We all suffer in this land. But let me tell you, God has a special place for us when our time has come.”

“The new heaven and the new earth should be understood as the closing of the circle; the tree of life in Genesis 2, once again appearing, now as the tree of continued life in Revelation 22,” LeBlanc explains. “This cyclical understanding lies at the heart of all Indigenous North American conceptions, and is clearly celebrated in the Ghost Dance, a dance of renewal and restoration.”

***

Damian Costello is the director of post-graduate studies at NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community. He lives in Montpelier, Vt.