Long.

Evicting Lote Ocho

How a Canadian Mining Company Infiltrated the Guatemalan State

Max Binks-Collier, The Intercept, Sept. 26, 2020

(https://tinyurl.com/yybwae5v)

It was often when Rosa Elbira Coc Ich was cooking lunch in the communal outdoor kitchen of Lote Ocho, a village in Guatemala, that the helicopters would fly overhead, the gusts of air from their deafening rotor blades scattering her tomatoes, beans, herbs, and tortillas over the reddish-brown soil. The helicopters would hover just above the village huts, billowing up clouds of dust and dirt and blowing some of the iron sheets and palm-leaf thatching that served as roofs onto the ground.

Ich remembers these helicopter flyovers taking place daily, sometimes even twice daily, beginning around the end of 2006 and continuing until 2008. Ich, who is now 35, told The Intercept that she would run into her hut, terrified that she and the other villagers were about to be forcibly expelled from their land by Compañía Guatemalteca de Niquel, or CGN: a Guatemalan mining company with which Lote Ocho and at least 18 other Indigenous communities had been embroiled in a dispute over land since early 2005.

The helicopters also reminded her of the military helicopters that she saw as a little girl toward the end of the 36-year civil war in Guatemala, during which the military committed genocide against several Indigenous groups.

Making Ich recall her country’s genocidal past and fear the use of force in the future seems to have been the point.

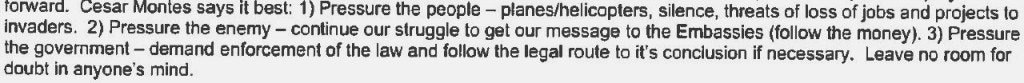

At the time, CGN was a subsidiary of Skye Resources, a Vancouver-based mining company. On October 12, 2006, Skye’s vice president of operations, William Enrico, sent several colleagues an email suggesting ways to deal with the “invaders,” as they called the Indigenous villagers:

“Cesar advised me to have more flignts [sic] – especially helicopter. It may be good if our regular flights did some circling over the important areas for psychological impact. This shouldn’t cost us anything extra.”

Document: Affidavit of Amanda Montgomery

The man who gave Enrico this advice was César Montes, co-founder of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, once a formidable left-wing militant group whose stronghold encompassed the Ixil region where, between 1981 and 1983, the military committed genocide against the Ixil people. Ixil refugees fleeing to the mountains were strafed by gunmen in helicopters. Montes, who seems to have worked informally as a consultant for Skye and CGN, would have had a keen understanding of the “psychological impact” that helicopters flyovers would have on Indigenous villagers.

The flyovers above Lote Ocho were revealed in previously private corporate documents that have become public through a lawsuit in Canada. These documents, largely unreported on until now, show that the harassment by helicopter was just one part of a much larger campaign that Skye and CGN undertook to expel Indigenous communities from a huge swath of land that the companies never had any legal right to either explore or exploit. The effort relied on mostly successful attempts to influence, manipulate, or pay the most powerful institutions of the Guatemalan state, including the judiciary, the security forces — and even the presidency. The campaign culminated in two waves of evictions targeting several Indigenous villages on January 8, 9, and 17, 2007. Eleven women from Lote Ocho were allegedly gang-raped by police officers, soldiers, and CGN’s security during the last eviction. Ich is one of those women.

Photo: James Rodriguez

She and the others are now suing Hudbay Minerals Inc., a Toronto-based mining company that bought Skye in 2008, acquiring Skye’s legal liability. During the ongoing lawsuit, the women’s lawyers obtained the emails, photos, and other documents cited in this story through the discovery process and filed them in court as exhibits in an affidavit. Hudbay has not yet formally responded to the affidavit, and the company declined to comment to The Intercept because the “matter in question is currently before the courts.” CGN did not respond to multiple requests for comment and written questions. None of the CGN or Skye employees or their Guatemalan associates that The Intercept attempted to reach for this piece replied or commented. In previous court filings and public-relations materials, Hudbay has disputed the 11 women’s claims, arguing that prosecutor and police records show that no CGN or other private security guards were present at the eviction on January 17 — and in fact, that “no illegal occupiers were present.” In other words, none of the women were even there, Hudbay claims.

The 11 women’s accounts of the trauma that the alleged gang-rapes caused them are unfathomable. Five were pregnant at the time; four miscarried, and one, three days from her due date when she was allegedly gang-raped, said in a deposition that she gave birth to a stillborn that “was all blue or green.” Marriages were irreparably ruined. The impoverished community eventually split and drifted apart as some members accepted jobs at CGN, even as the company allegedly intimidated and harassed the women to pressure them into dropping their lawsuit. Thirteen years after the evictions, the women claim to live with chronic pain and ongoing emotional suffering. Sometimes, the two merge. During a 2017 deposition, one woman said: “Something has entered inside me, and it is a fear. It’s a terror, and it is a physical pain that I live with all the time.”

The Legacy of the Land

Before January 17, 2007, Lote Ocho, a village of about 100 homes, was perched high on a mountain, giving the families there a breathtaking, panoramic view of the rolling, green Guatemalan highlands and, “in the distance, the glinting mirror of Lake Izabal,” as photojournalist Roger LeMoyne described it. Lote Ocho was secluded, an approximately 45-minute drive up a treacherously bumpy, unmaintained road from the nearest town, Cahaboncito. But the people of Lote Ocho rarely went into town. They lived off the land.

An intimate, spiritual connection to the land is at the heart of the worldview of Lote Ocho’s villagers, who, as Maya Q’eqchi’, belong to one of the more than 20 Indigenous groups in Guatemala descended from the pre-Columbian Maya civilization. But in 2004, Skye was granted permission to begin work in a large area in northeastern Guatemala that was home to many Maya Q’eqchi’ communities, including Lote Ocho.

Earlier that year, Skye had bought the rights to the open-pit Fenix nickel mine, located near the majority-Maya town of El Estor, on the shore of Lake Izabal, from the Canadian mining company INCO. Skye had also bought INCO’s 70 percent share of its subsidiary, EXMIBAL, which Skye then renamed CGN. But the deal also saw Skye acquire the long-festering, unresolved disputes over land left by INCO and EXMIBAL’s violent past.

INCO began negotiations over a potential open-pit nickel mine with the military dictatorship of Guatemala in 1960, the year that civil war broke out. After an INCO-hired engineer contributed to the drafting of a new mining code permitting “open sky mining,” forbidden by Guatemala’s then-suspended constitution, EXMIBAL was granted a 40-year mining license for an area covering 385 square kilometers in 1965.

The next year, Col. Carlos Arana Osorio launched an ostensible counterinsurgency campaign in the area, which would earn him the nom de guerre “the butcher of Zacapa.” During this campaign, the military expelled peasants from land that would become the site of EXMIBAL’s facilities. Between 3,000 and 8,000 people, mainly noncombatant Maya Q’eqchi’ peasants, were killed. In the ’70s and ’80s, EXMIBAL vehicles were used for drive-by shootings targeting local civilians; at least one of them involved the police. In 1978, EXMIBAL employees and soldiers executed four people in the town of Panzós where, one month earlier, the military massacred Maya Q’eqchi’ peasants who were protesting over land claims. The full extent of EXMIBAL’s violence will likely never be known: “I, personally, know of even more cases that are not documented and are guarded under the seal of the confessional,” Daniel Vogt, a priest and then-director of a Maya Q’eqchi’ rights organization, told Skye’s COO in September 2006, in an email that came to light in the Canadian lawsuit. “What has remained is a history of pain and desperation.”

It was against this historical backdrop that Skye and the rechristened EXMIBAL, CGN, acquired a license to explore an area of 259 square kilometers that encompassed at least 19 Maya Q’eqchi’ settlements on December 13, 2004. The Canadian embassy in Guatemala had lent Skye a helping hand: “After months of negotiation, during which the Embassy played a strong supportive role, the Guatemalan Ministry of Energy and Mines has issued a 3 year exploration licence to Skye Resources,” a counselor from the Canadian embassy wrote to his colleagues on December 16, 2004, in a previously unreported email obtained by the women’s lawyers. “Any victory for responsible mining interests is a victory for Canadian investors.”

But Guatemala’s Constitutional Court would later rule that the license was granted illegally. The Guatemalan government did not consult the Indigenous people occupying or using the lands before granting the license, which it was required to do under the U.N.’s International Labour Organization Convention 169, or the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, to which Guatemala has been a signatory since the 1996 Peace Accords. The ILO found the license contravened Convention 169 in 2007, and the Constitutional Court came to the same conclusion on June 18, 2020.

“What has remained is a history of pain and desperation.”

Given this history, it was virtually inevitable that the exploration drilling in early 2005 would spark many conflicts between the companies and local communities, who alleged that CGN was encroaching on their land and destroying the environment, including by polluting their water supplies. Nevertheless, on April 17, 2006, Guatemala granted Skye and CGN another license — also later found to be invalid by the Constitutional Court — which allowed them to start mining.

In response to CGN’s increasingly active operations, five Maya Q’eqchi’ groups composed of about 300 families moved onto company-claimed land on September 17, 2006. They argued that they were reclaiming lands that INCO had stolen from them over 40 years ago. Over the next two months, these groups grew to nearly 1,000 families.

From the time these settlements were founded right up until the evictions in January 2007, which targeted some of these recent settlements but also another decades-old village, many people on both sides of the dispute urged the companies to resolve the standoff through dialogue, according to emails in the court documents.

“Any attempt to forcibly evict the villagers would end in tragedy,” Vogt, the priest, emailed Skye management on September 22, 2006. Just three days before the evictions, CGN’s own consultant emailed a company manager: “As we have already said, there will NEVER be a positive eviction.”

Even though Skye management stated that the “invasions” were not affecting operations, primarily because most of them were “not on essential project land,” Skye decided that if the villagers would not leave on their own, Skye and CGN would force them off.

Photo: James Rodriguez

“Keep the President Informed”

Two men from the town of El Estor were high up on a remote mountain when they say they saw about 50 people force their way onto CGN’s land on September 23, 2006. The village of Lote Ocho was now located on the land where this group had “enter[ed] by force,” indicating that Lote Ocho was another land occupation. Or at least, that’s what the men allege in affidavits that CGN filed in a Guatemalan court in the fall of 2006.

Those affidavits “falsely asserted that the affiants had personally witnessed members of the community of Lote Ocho using force to occupy their village when in fact the affiants had never been to Lote Ocho,” lawyers for the 11 women alleged in their own affidavit.

“This is important because these are the foundational documents that start everything,” said Cory Wanless, who, along with Murray Klippenstein, is representing the women in court. “It undermines the whole legal foundation of seeking an eviction in the first place.”

The two lawyers have been litigating this and two other cases against Hudbay (the company that bought Skye) since 2011. The lawsuits have garnered international coverage because they could set a precedent in making it easier to hold multinational corporations accountable in their home countries for wrongdoing abroad.

He argues that the affidavits that initiated the eviction proceedings are unreliable for a few reasons. Most importantly, Lote Ocho has been located in the same area for decades; it wasn’t settled on that day in September 2006, although several additional families did join Lote Ocho that month as part of the broader reclamation movement. And if 50 people entered the area “by force,” why were these two men — who just so happened to be passing by on top of a secluded mountain — the ones swearing the affidavits instead of a company employee against whom this group would presumably have had to exercise force?

The lawsuits could set a precedent, making it easier to hold multinational corporations accountable in their home countries for wrongdoing abroad.

While these affidavits appear highly implausible by themselves, they are also virtually identical to two other affidavits that CGN filed, each supposedly listing the names of the occupants of a different village that Skye and CGN wanted to evict. The affidavits recycle the same list of names, with only minor differences. Taken together, they assert that the same individuals simultaneously occupied three different settlements. Wanless thinks CGN filed these affidavits because, in Guatemala’s often dysfunctional courts, “that’s enough to get the job done.”

They did, in fact, get the job done, and Wanless may be right about why they worked. There is often a “lack of due diligence on the part of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and judicial authorities to investigate [land] disputes; eviction orders are often authorized after a superficial consideration of the facts,” states a 2008 Amnesty International submission to the U.N.

Many judges “just take into account the title that the private sector is presenting,” said Ramón Cadena, director of the Central American office of the International Commission of Jurists. This also facilitates “pressure by private-sector entities,” he said.

Despite the affidavits being accepted, CGN had trouble obtaining the eviction order for Lote Ocho. On December 1, 2006, Enrico, the Skye executive, emailed other senior management at the company an update.

Document: Affidavit of Amanda Montgomery

“We’ll need pressure on the Puerto Barrios Judge,” he wrote. “We have this arranged.”

One week later, the judge granted the eviction order, according to the affidavit filed by the women’s lawyers.

But CGN soon had to clear another legal hurdle: The villagers and an Indigenous rights group, CONIC, had gone to court and requested an amparo — similar to an injunction — to temporarily prevent the impending evictions because they had not been notified of them. In late December, it seemed likely that they would be granted their request, which would have postponed the evictions for at least six months.

According to emails filed in court, CGN managers called their “contacts” at the Policía Nacional Civil, Guatemala’s national police, to see if the PNC could conduct the evictions ahead of schedule, before the amparo could be granted. However, the police replied that too many officers were on holiday. Additionally, “they said the order to speed up the execution of the orders will have to come from a very high level either the President or the Minister of the Interior,” Monzón wrote.

Monzón called Rodolfo Sosa, a CGN lawyer, who said he would try to speak to the Guatemalan president, Óscar Berger. Sosa and Berger were once partners in the same prestigious firm, and Sosa’s daughter is married to one of the president’s sons. Sosa could not reach Berger, however. So Monzón contacted his “friend,” the minister of defense, who also couldn’t help because of the vacationing officers.

Since those avenues were dead ends, CGN requested that the court let it weigh in during the legal proceedings that CONIC had initiated.

Document: Affidavit of Amanda Montgomery

“We hope that with this actions [sic] we will be able to delay CONIC process for at least 2 weeks, which means the eviction orders will be executed within that period of time,” Monzón wrote. Enrico replied that it was important to keep Rodolfo Sosa informed of the “slowing strategy,” since “Rodolfo is our avenue to keep the President informed.”

This “slowing strategy” worked: The evictions took place before the amparo could be granted.

The emails show that Skye and CGN had woven themselves into a network of informal connections that they drew on while attempting to influence government officials. This illustrates how “collusion between business and the state” works in Guatemala, University of Oslo professor Mariel Aguilar-Støen told The Intercept. Aguilar-Støen co-authored a 2016 article that examined how local elites often participate in mining projects by, for example, working as company managers or lawyers, allowing the companies to exploit “the networks of contacts that the domestic elites control,” the article states. The way CGN leveraged its connections “is a very good example of how mining companies in particular operate and how they gain access to resources,” she said.

Photo: James Rodriguez

Black, Blue, and Green

CGN already had a preview of just how violent evictions could be. On the morning of November 12, 2006, a public prosecutor and about 60 police officers showed up at a Maya Q’eqchi’ settlement of approximately 30 families that was located across the road from CGN’s housing complex, on the outskirts of El Estor. The families had settled there early the previous morning, when it had been the scene of clashes with the PNC and CGN employees.

An uneasy peace had reigned since later that morning, when government officials charged with resolving land disputes were said to have struck a tentative agreement with some leaders of the Maya Q’eqchi’ settlements that were established in September. But with the arrival of the prosecutor and the police, the situation soon spiraled out of control.

During the standoff that ensued, it became clear that the prosecutor did not have a judicial eviction order, which he argued was not necessary — but he was incorrect, according to a contemporary Amnesty International report that explains the legal process for conducting evictions in Guatemala. The priest Daniel Vogt and a partner apparently defused the tension enough that by midday, the families left with their supplies, but a clash erupted between the police and locals not long afterward, and later that day, the police fired tear gas into another settlement by CGN’s airstrip to evict its inhabitants.

Then the police shot tear gas, without warning, into another settlement to evict some 200 families, according to a contemporary report by Vogt’s Maya Q’eqchi’ rights organization. During these skirmishes, goods were stolen and several people were injured, including a pregnant woman who had been engulfed in tear gas, the report states. Two people disappeared. The next afternoon, one of the missing people was found lying unconscious and badly beaten beside a trail. There were more skirmishes with the police that day.

About 20 people broke into CGN’s community relations center and a newly renovated but still-empty hospital and set the buildings on fire. Internal company correspondence reveals that this group was likely what company management called a “youth mob” that was “not related to the invaders.”

“Later on at night everything went back to normal-a military group was deployed to EE [El Estor] to safeguard our personnel,” reads a company email.

In response, a community relations consultant sent an email stating, “Having the military deployed as peacekeepers opens an area of risk for us – we need to make sure we create a clear distinction between company security forces and the military.”

Documents strongly suggest that the public security forces were paid large sums of money for their work in the evictions.

But that distinction was already very blurred, as is clear from an email sent on November 17, 2006, just days after the military’s deployment and the heavy-handed, unlawful evictions. CGN’s financial manager wrote to Skye’s chief financial officer: “We have paid to keep the invaders under control this week Q125,000,” which was approximately $16,447.37 at the time.

The money had covered the hotel rooms, meals, and gasoline of 125 PNC officers. CGN had also paid for the meals of about 65 soldiers who were sleeping in CGN’s cafeteria for security reasons.

The money for the police was transferred “to personal account [sic] who is working to coordinate these tasks,” wrote CGN’s financial manager.

The “personal account” likely belonged to one of at least several middlemen whom Skye and CGN had retained to take advantage of their connections to the PNC and military, according to the affidavit submitted by women’s lawyers. One middleman was a friend of the second-in-command of the PNC, and another was a disgraced colonel involved in a “powerful mafia ring in the army and police” in the 1990s, according to Latin American Digital Beat.

From October 2006 until at least up through the evictions in January, the companies spent close to $140,000, and likely far more, in clandestine payments to these middlemen, who passed on nearly all of it to the security forces, according to numerous emails, bonus sheets, and spreadsheets entered into the court record.

While a lot of money went towards paying for logistical supplies, such as gasoline and lodging, certain documents strongly suggest that the public security forces were paid large sums of money for their work in the evictions themselves.

For example, a security and human rights audit that Skye requested states, “There are rumors of 1.2 million quetzals” — about $157,895 at the time — “funneled to the armed forces for their work in land evictions, when all that was officially agreed to was logistical support such as gasoline.” These rumors were pretty persuasive: “Based on the rumors of misused funds, the company fired the actors that instigated this type of activity,” the audit notes.

One spreadsheet shows “the total funding in cash” as of December 31, 2006, “for evictions.” It records payments for vaguely worded services like “funds invasions security.”

Legal experts have raised the possibility that just the payments for the logistical supplies violated Guatemalan and Canadian anti-corruption laws. Paying for the supplies of the public security forces amounts to bribing them, since Skye and CGN effectively bought a degree of influence over them, argued Guatemalan lawyer Verenice Jerez, who worked with CICIG, a now-disbanded United Nations-backed anti-corruption commission. “In this world, nothing is free,” she said. Alan Franklin, a Canadian corruption law expert who sometimes works with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, echoed what Jerez said. But Jennifer Quaid, another Canadian expert, said that it was unclear whether the payments ran afoul of the version of the relevant Canadian law that was in force at the time. No charges have been laid against either company for making them. Hudbay and CGN did not respond to written questions from The Intercept about the payments.

Regardless of whether any laws were broken, the companies were heavily involved in the planning and execution of the operations of the public security forces. This close working relationship extended up to the highest-ranking officers. In December 2006, CGN’s site manager “coordinated” with Rodolfo Sisniega-Otero, the son of a notorious general and a commander of the Brigada Guardia de Honor, an elite corps of military police. And one day before the alleged gang-rapes, one of CGN’s middlemen and Edin Palma, a PNC chief, went on a reconnaissance flyover of the “invaded areas.”

A photo introduced in court shows Guatemalan police trucks lining up outside a CGN compound.

Photo: Affidavit of Amanda Montgomery

Skye and CGN management also participated in coordinating the on-the-ground activities of the rank-and-file police officers and soldiers who effectively worked as partners of CGN’s security. Photos show that shortly before the eviction on January 9, dozens of PNC trucks and vans stretched in a long row along the road outside of CGN’s compound, inside of which a white pickup truck carried men “in what appear to be army uniforms,” according to the affidavit filed by the 11 women’s lawyers. The public and private security forces gathered at CGN’s facilities “on the morning of each eviction, including the eviction on January 17,” the affadavit alleges. Photos also show CGN managers, their middlemen, and PNC officers having a meeting after the eviction of January 8, 2007. This was just one of the “pre-eviction planning sessions and post-eviction debriefs [that] were held in CGN’s offices,” the affidavit claims.

The armed, masked men who stormed into Lote Ocho as the rain poured and the wind gusted at 5 o’clock in the evening on January 17, 2007, only seemed to be distinguished by their uniforms. The uniforms were black, “the colour of the sky,” and “the colour of the trees,” the women say. Black, blue, and green: the outfits of the PNC, CGN security, and the army. Something else helped tell them apart: Two of the women who are literate say they saw CGN’s logo on the blue uniforms.

This distinction mattered little, however, since the three groups of men had allegedly already broken into smaller groups and teamed up when they attacked, according to the women’s depositions. Men from each force seized one pregnant woman who was making tortillas and dragged her into the bushes as her children cried and screamed, she testified. She described the men as a “dog when he comes and he finds some food and he’s growling.” It was all together that they gagged her, wrapped cloth around her eyes and ears, cut her clothes off with a machete, and raped her one after another in what was perhaps an intentional reenactment of the rapes that the military used as a tactic of terror against Maya women during the civil war. “They took off my clothing and they played with my life,” another woman said during her deposition. Men from all three groups splashed gasoline over the makeshift huts and the women’s tattered clothing and set them ablaze.

Irma Cac, one of the woman who was allegedly gang-raped, cried while speaking in Toronto in September 2019 after attending a hearing in the ongoing lawsuit. “I will never forget,” she said, “it will never escape from my eyes — the color of the uniforms of the soldiers, of the police, and of the private security.”

Update, September 26, 2020, 3:45 p.m.

This article has been updated to include that Murray Klippenstein is also representing the 11 women.