By Helen Redmond, Filter, March 27, 2019

By Helen Redmond, Filter, March 27, 2019

There is a profound moment in the film And The Band Played On, about the early days of the US AIDS epidemic.

Dozens of AIDS activists attend a raucous public hearing between the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the owners of blood banks.

The CDC presents strong evidence that AIDS is a blood-borne disease and warns that hemophiliacs who require numerous blood transfusions are at high risk of HIV infection.

Executives from the blood bank industry argue that there isn’t enough evidence that the blood supply is contaminated, and that they can’t spend millions of dollars screening blood. Even though eight hemophiliacs have already died.

Don Francis, a CDC epidemiologist, stands up and shouts:

“How many dead hemophiliacs do you need?

“How many people have to die to make it cost-efficient for you people to do something about it?

“One hundred, a thousand?

“Just give us a number so we won’t annoy you again until the amount of money you spend on lawsuits makes it more profitable to save people than to kill them.”

Almost 5,000 hemophiliacs became infected with HIV before blood products were screened for the virus, and more than 4,000 of the estimated 10,000 hemophiliacs in the US would eventually die of AIDS.

For other groups infected with HIV — above all, gay men and injecting drug users — total deaths were far higher.

AIDS poster by Gran Fury via NOMOI

Don Francis’s questions need to be updated for the opioid-related overdose crisis:

How many dead opioid users do you need?

How many people have to die to make it cost-efficient for you people to do something about it?

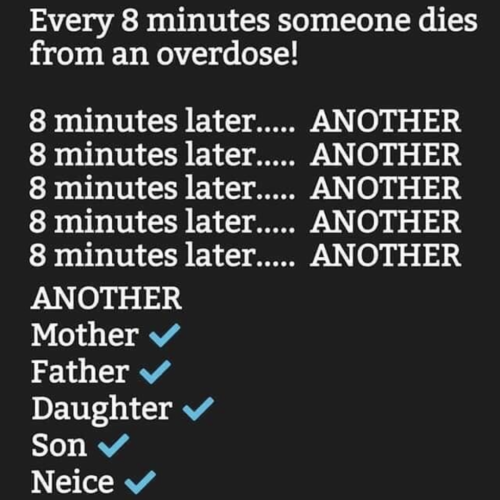

Just give us a number: 70,000 people died from drug overdose in the US in 2017 — nearly 200 a day.

Many commenters propose one place to point the finger.

On March 26, Purdue Pharma agreed to a $270 million settlement of a lawsuit that accused the company of deceptive marketing of its drug, OxyContin — blamed by many for precipitating the crisis.

And prominent museums have of late been rejecting donations from the philanthropic trust of the Sackler family, which made its billions from selling opioids.

Accountability for wrongdoing is important — though the extent to which Pharma, rather than societal factors, drives addiction is questionable.

What’s far more needed is identifying structural, political and societal lessons that we have been far too slow to grasp — and then acting on them.

Structural Failures and Deliberate Damage

The AIDS crisis that unraveled over two long, dismal decades shared many features with the overdose crisis of today.

Intransigent federal, state and local governments refused to marshal the resources and strategies needed to effectively address AIDS; ditto for today’s crisis.

The core systems that are vital in responding to mass overdose deaths – drug treatment, healthcare and mental health services – have failed spectacularly at every level.

And stigma — better described as sheer hatred of drug users — is the glue that binds together politicians, police and the public in blocking solutions that could save lives, especially those based in harm reduction.

Based on these attitudes, another system drives the crisis: The War on Drugs.

Wasting billions of taxpayer dollars, drug warriors — from local law enforcement to special narcotics task forces to agents at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to prosecutors and public and private prison systems — wage war on people who use drugs, above all poor people and people of color.

Whole industries depend on this criminalization and incarceration.

Just give us a number: Since 1971, the War on drugs has cost the United States an estimated $1 trillion.

Incredibly, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) – a police agency – regulates the dispensation of methadone and buprenorphine.

The DEA has opposed attempts to expand access to these life saving medications (for example, methadone vans) with the rare exception of raising patient caps for buprenorphine prescribers.

Prosecutors are increasingly charging people who sell or administer drugs that lead to overdose deaths with drug-induced homicide.

The most common reason people cite for not calling 911 in the event of an overdose is fear of police involvement.

Bystanders who could save lives are unlikely to dial 911 if they fear being charged with murder or manslaughter.

The end result: More drug users die.

As a nation, we didn’t learn the lessons of the AIDS crisis.

Namely that our healthcare, mental health, and drug treatment systems need a major upgrade and paradigm shift.

To be sure, AIDS activists confronted these broken systems, including the pharmaceutical industry, but they did not fundamentally transform them.

A Disastrous Healthcare System

The US healthcare system is a disaster. The world’s richest country has somehow gotten away with not providing healthcare to all as a human right.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle argue it will cost too much. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, known as Obamacare, didn’t end the crisis in healthcare.

Just give us a number: 28.5 million people in the United States have no health insurance.

The private, for-profit American healthcare system lavishes cash onto a small group of health insurance company CEOs and stockholders while denying care and limiting benefits to millions of Americans.

Just give us a number: The annual pay for Michael F. Neidorff, CEO of Centene, a health insurance company, is $25.26 million.

Insurance coverage consists of a complex patchwork of federal and state programs – Medicaid, Medicare, Veterans Administration – alongside thousands of private plans. Understanding the costs and coverage of a health plan is massively confusing and time-consuming.

Even choosing a plan is a conundrum — check out the healthcare website for New York State.

Millions lose coverage every year as a result of changing eligibility criteria or job loss, and then scramble to find new coverage.

It’s called “churning.”

As a result of churning, there are gaps in care, which can be life-threatening for people with chronic physical or mental health problems and for people on medication-assisted treatment.

Out-of-pocket costs for drug treatment, visit caps and high co-pays for counselling and medication restrict entry to services or simply put them out of reach.

People with an opioid addiction are considered “high utilizers” of healthcare resources because of the relapsing nature of addiction. Insurers loathe providing care to these patients because it cuts into profit margins.

The high rate of uninsured, the pursuit of profit over the needs of patients, and the inability to coordinate and distribute healthcare resources where they were most needed severely compromised the fight against AIDS.

These factors now compromise our ability to end the overdose crisis.

A single-payer, universal healthcare system is the only way to effectively impact public health crises in the US.

Countries that provide healthcare to everyone have shown that they can effectively mobilize resources to limit death tolls.

Medicare for All legislation would create a national healthcare infrastructure that could effectively address the crisis.

But not only is the structure of American healthcare unable to respond effectively to the crisis; neither are healthcare providers.

Their widespread ignorance of addiction and evidence-based treatment is astonishing. Moreover, doctors, nurses and other medical staff too often hate and fear people who use drugs.

I worked in healthcare for over a decade as a medical social worker in hospitals, outpatient clinics and an ER in Chicago, and witnessed judgemental and discriminatory attitudes towards drug users on a daily basis.

Doctors in particular have a long record of abandoning opioid-dependent patients. They are doing it now by cutting off pain patients in droves, leading some to suicide. It is medical malpractice.

The medical profession has much else to answer for — from opposing single-payer healthcare to overprescribing and profiting from “pill mills,” to refusing to prescribe the medications that can keep drug users alive.

Too many healthcare providers have blood on their hands.

This double whammy of a dysfunctional healthcare system combined with healthcare provider hatred or indifference is a prescription for more opioid-related deaths.

An Obsolete, Profiteering Rehab Industry

But it’s actually a triple whammy.

Imagine this: A drug treatment system that is based on an obsolete, religious dogma developed by white men, insists on abstinence, kicks people out of treatment for relapsing, is riven with New Age quackery and scam artists, and bans access to medications that are the gold standard of treatment for opioid addiction.

Wait, you don’t have to imagine that: It’s the current US addiction treatment “system.”

You know, the one where drug users show up at fire and police stations to beg for help?

The American love affair with abstinence-only treatment holds that the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and its spin-off, Narcotics Anonymous (NA), is drug treatment. It is not.

The same basic text has been used by AA since the publication of its “Big Book” — in 1939.

News flash: It’s 2019 and many thousands are dying.

Treatment centers are often staffed with former drug users who have “lived experience” but minimal training or education.

A report by the Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University stated, “The majority of those who currently make up the addiction treatment provider workforce are not equipped with the knowledge, skills or credentials necessary to provide the full range of evidence-based services to treat the disease.”

The report also notes that the lack of physician training in addiction medicine and negative attitudes toward drug users impede care.

A shift in insurance coverage for addiction occurred in 2008.

Congress passed legislation requiring private insurers to offer the same benefits for mental health and addiction treatment as they do for other medical services.

The Affordable Care Act codified mandatory drug treatment coverage.

This set off a rehab spending spree that coincided with the increase in opioid addiction.

Private insurance spending on patients with opioid addiction grew tenfold, to $722 million a year.

Enter the for-profit drug rehab industry and the unleashing of “patient brokering” and the “Florida Shuffle.”

Patient brokering is when a drug rehab facility pays a person, often a drug user in recovery, for recruiting patients to their program.

The Florida shuffle goes something like this:

1. A patient is recruited by a broker for a 30-day stay in a Florida rehab.

2. The patient then moves to a sober living facility.

3. The patient eventually relapses.

4. Next, the patient is admitted to another Florida rehab facility.

This dangerous cycle repeats and the patient’s insurance or the patient is charged over and over.

Cha-ching!

Patients have died in this sick game of corporate greed.

In 2017, Nick Sarnicky, 23, was a victim of the “California shuffle.” He went through four rehabs in five weeks in Los Angeles, racking up insurance charges in excess of $100,000.

His patient broker sold him heroin. Sarnicky was found dead of an overdose in a motel room. According to the police report, he was scheduled to go into detox the day he died.

Just give us a number: The for-profit US rehab industry is worth $35 billion a year.

This drug rehab circus includes minimal oversight of “sober” homes — in fact, anyone can open one.

What regulatory authority cares if drug users in rehab are neglected or abused?

Which politician is going to stand up and demand respect and dignity for people with heroin addiction?

The overdose crisis has exposed the reality that drug treatment is deplorable and the lives of drug users disposable.

Lethal Blocking of MAT

Methadone is the most successful treatment for opioid addiction.

Its efficacy is backed up by four decades of indisputable research. But there is a fundamental problem with the dispensation of the drug in the US.

Methadone is a tool of harm reduction, but the system that controls methadone is a system of harm production. Methadone clinics are mini surveillance and carceral states.

Clinics have security guards inside and out and frequently hire off-duty cops. Ceiling-mounted cameras record everything.

Staff observe ingestion of the medication, even asking patients to lift their tongues to prove they’ve swallowed.

Patients are required to attend clinic six days a week during specific windows of time to get medicated. Random, “supervised” urine toxicologies and counselling are mandatory.

If a patient has “earned” take-home doses of methadone and their urine tests positive for illicit drugs, it’s back to attending six days a week.

Just give us a number: People in rural areas typically have to travel 50-200 miles each way to get to a methadone clinic.

If a person is late (car broke down, train delayed), too bad: no methadone.

Think about that consequence in the context of a country where most heroin is cut with fentanyl.

What would you do? Go into withdrawal or buy heroin and risk overdose?

This is a choice methadone patients all across country are forced to confront every day. Methadone clinics that turn patients away because they are late have blood on their hands.

Some states though, have opened more methadone clinics and expanded hours.

In Phoenix, Arizona for example, the for-profit corporation Community Medical Services, with the help of a federal grant, became the first 24/7 medication-assisted treatment center in the country.

“For some reason, this clinic has started engaging people who otherwise would not have gotten into treatment. That’s why I think it exploded…I really think this model should be replicated,” explained Nick Stavros, the company’s chief executive.

The clinic allows people to come in even if they are high, gives them time to come down, and can then give them a dose of methadone.

I’ll tell you why the clinic is attracting so many new patients: It’s meeting people where they’re at and allowing users to “come as you are.”

Both are basic tenets of harm reduction. It uses a drop-in model of treatment, with flexible hours and acceptance of patients who are intoxicated.

Just give us a number: In 17 states Medicaid doesn’t cover methadone treatment. In West Virginia, the state with the highest opioid-death rate in the country, Medicaid only began paying for it in January 2018.

Prescribing of buprenorphine, another drug with proven efficacy at saving lives, has different barriers.

In order to prescribe the medication, healthcare providers must complete hours of training, and receive a DEA waiver which grants the police agency the right to access all patient records.

Prescribing is office-based and the medication can be picked up at pharmacies, a major plus. But one of the main problems is the number of prescribers.

Just give us a number: Only about five percent of the nation’s doctors – 43,109 – are licensed to prescribe buprenorphine.

Half the counties in the United States don’t have a single buprenorphine prescriber.

Providers have a 30-patient cap in the first year, and most insurance companies require prior approval before the drug can be prescribed.

Waivers, caps and preauthorizations delay care. Access to and retention in medication-assisted treatment matters greatly because it reduces the risk of overdose death by half.

Contrast these prescribing policies with France. In 1995, during a heroin overdose epidemic, the government allowed all doctors to prescribe buprenorphine with no special training or licensing.

Four years later, heroin deaths had dropped by 79 percent.

The US federal government released a report on March 20 that found more than 80 percent of the roughly two million people with opioid addiction are not being treated with the medications most likely to save their lives.

The report concluded that, “There is no scientific evidence that justifies withholding medications from opioid use disorder patients in any setting or denying social services (e.g., housing, income supports) to individuals on medication for opioid use disorder. Therefore, to withhold treatment or deny services under these circumstances is unethical.”

So how is it that barriers to buprenorphine and methadone remain in place?

Why don’t we massively expand access to these two lifesaving medications?

The answer: Stigma.

Methadone is probably the most stigmatized drug in the pharmacopeia and buprenorphine isn’t far behind.

The medications are widely believed to be “trading one addiction for another.”

The Need for Activism Now

The fight to open safer consumption sites in the US is yet another example of a harm reduction intervention being opposed by the criminal justice system.

In Philadelphia, federal prosecutors filed a civil suit against Safehouse, a nonprofit organization seeking to open a safe consumption site.

The drug warriors don’t care that the evidence shows they save lives.

Canada currently has 24 safe consumption sites.

Harm reductionists and grassroots organizations, often started by families of loved ones who died of overdose are infuriated at the glacial pace of reforms to stem these deaths.

This isn’t like the AIDS epidemic, where it took over a decade of research to find drugs to keep people alive.

The medications and resources to keep people with opioid addiction alive are known and available right now.

Yet it’s still harder to get methadone or buprenorphine than street heroin.

And if pharmaceutical-grade heroin were available, as it is in Switzerland, Canada and many other countries, that would save many lives — yet that seems politically even less likely in the US than increasing methadone and buprenorphine access.

The people in power who refuse to make these medications available on demand have blood on their hands.

Just give us a number: It seems there is no number of overdose deaths that will end the government neglect of people who use drugs.

And this is where we need to learn the lessons of AIDS activism. Because for a long time the government didn’t care that gay people were dying by the thousands.

The organization Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) organized demonstrations; die-ins; threw buckets of red paint on pharmaceutical headquarters; got arrested; confronted politicians, physicians, and the church.

They made life hell for the people who would stand by, do nothing and watch them die.

Similarly, in the 1980s, groups of harm reduction activists began making the breakthroughs that have spared us an even worse toll of human lives in this overdose crisis.

They started illegal syringe exchanges. They handed out free syringes and went to jail.

And all of this activism led to real reforms.

The Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) in Canada engaged in similar civil disobedience tactics.

They forced their government to open a safe injection facility–the first legal one in North America.

All the research and reports that unequivocally show that harm reduction interventions work to decrease overdose deaths haven’t motivated politicians or the current president to implement them.

Therefore, it’s past time to engage in civil disobedience to end the overdose crisis.

One part of that is setting up safe consumption sites despite their illegal status.

That is precisely what activists in Toronto did last year, and what different groups are doing in Seattle and many other places.

We need to change laws, but we don’t have time to wait for laws to change.

There is nothing to lose and thousands of lives that can be saved.

We are standing on the shoulders of AIDS activists who fought the very same opponents we are fighting today.

And it’s still a matter of life and death.

Some math: