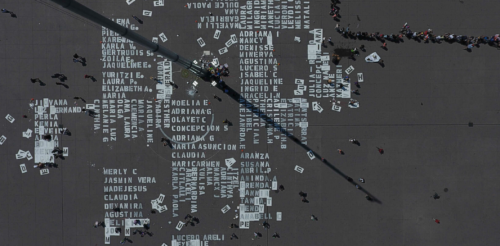

Women raise their hands as they protest against gender violence and femicide in Puebla, Mexico [REUTERS/Imelda Medina]

“A country without women, for one day.

“An alliance of feminist groups in Mexico that — fueled by the rising violence against women and girls, including two horrific murders that appalled the nation this month — have called for a 24-hour strike by the country’s female population on March 9.”

Women in Mexico Are Urged

to Disappear for a Day in Protest

Women protested gender-based violence in Mexico City earlier this month. Credit…Andres Martinez Casares/Reuters

By Paulina Villegas and Kirk Semple, The New York Times, February 26, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/26/world/americas/mexico-un-dia-sin-nosotras.html

Fed up with escalating gender-based attacks and murders, activists called for a daylong national strike by women to demand greater support for their rights.

MEXICO CITY — No women in offices or schools. No women in restaurants or stores. No women on public transportation, in cars or on the street.

A country without women, for one day.

That’s the vision of an alliance of feminist groups in Mexico that — fueled by the rising violence against women and girls, including two horrific murders that appalled the nation this month — have called for a 24-hour strike by the country’s female population on March 9.

The action is to protest gender-based violence, inequality and the culture of machismo, and to demand greater support for women’s rights.

Promoted under the hashtag #UNDÍASINNOSOTRAS, A Day Without Us, it has gained extraordinary momentum across this country of more than 120 million, with wide-ranging buy-in from the public and private sectors, civic groups, religious leaders and many, if not most, women.

The support has cut across the boundaries of class, ethnicity, wealth and politics that fracture this nation, and has given organizers hope that this might be not just a monumental event but also a watershed moment in the modern history of Mexico.

In Bone-chilling Numbers,

Femicides in Mexico

are a National Emergency

By Carli Pierson, National Catholic Reporter, February 14, 2020

https://www.ncronline.org/news/opinion/bone-chilling-numbers-femicides-mexico-are-national-emergency

On Feb. 9, 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla was stabbed to death, skinned and disemboweled by her boyfriend in Mexico City. And while local media has been consumed with the gruesome details of Escamilla’s brutal killing, that wasn’t the only femicide committed in the country that day.

That same day, a 64-year-old woman was killed in the state of Puebla by her partner; a woman was found dead in a canal in Veracruz state with signs of torture; and two sisters who had been missing for two weeks were found dead in the state of Jalisco.

On Feb. 9 in Mexico, a woman was killed in Mexico state; in the state of Morelia, there were minimum two femicides. On Feb. 9 in Mexico, there were nine femicides that we know of. On average, 10 women are murdered every day in Mexico.

In another high-profile femicide on Nov. 25 of last year, on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, Abril Pérez Sagaón was shot to death in her car in front of her two teenage children. Her husband and former head of Amazon Mexico, Juan Carlos García, is suspected of hiring the assassin.

García had been arrested for beating her with a bat and had been held in pretrial detention for 10 months, but was released early after Judge Federico Mosco González downgraded the charge of attempted femicide to a domestic violence charge. The judge argued that if her husband had wanted to kill her, he could have because she was sleeping when he began beating her with a bat.

For years, bishops and priests have spoken out in response to the alarming number of femicides in the country — a crime that is generally defined as the “killing of females by males because they are female.”

In December of last year, human rights activist Fr. Alejandro Solalinde apologized to Mexican women who have suffered “discrimination, mistreatment or have been killed.” He also apologized for the Catholic Church, “which has been the one that has transmitted patriarchal, macho prejudices.”

In Mexico,

Women are Hated to Death

Women raise their hands as they protest against gender violence and femicide in Puebla, Mexico [REUTERS/Imelda Medina]

Days later, leaked pictures of Ingrid’s mutilated body appeared in sensationalist tabloid newspapers with headlines such as “It was cupid’s fault”.

At around the same time, on February 11, an unidentified woman collected a seven-year-old girl known only as Fatima (we have since learned her family name is Aldrighett) from her school in Xochimilco in Mexico City. Four days later, Fatima’s body was found naked and bearing signs of torture inside a black plastic bag. She had been dumped by the edge of a dirt road three kilometres (1.9 miles) from her school.

In Mexico, both these cases are considered femicide, a distinct crime which describes the killing of a woman because she is a woman.

These cases are shocking and appalling, or at least they should be. But the public and official response is not always one of empathy towards the victims.

We witness on a regular basis how a country that is riddled with sexism literally hates women to death: 10 women are murdered every day – in the vast majority of cases by men.

In the aftermath of Ingrid’s case, it has become common in Mexico to hear people talking about her poor choice of partner and about how she, being so young and beautiful, should have found someone else.

This attitude is infuriating, not only because the blame is being placed on Ingrid, the victim, for staying in an abusive relationship, but also because that message does not reflect at all on the man who killed her as a current and future abuser of women. It seems to say: If only she had left, he would have stopped being a violent person.

Ingrid’s case has highlighted how very deep this fatal lack of empathy goes. People made jokes and memes about her death on social media sites, some as gruesome as depicting her as a “cabrito” – a north Mexican dish of roasted young goat cut open down the middle with the insides exposed.

Ordinary people were morbidly searching for and sharing the pictures of Ingrid’s body online. The idea that the blame for her own gruesome murder lay squarely with Ingrid herself flooded the internet during that second week of February.

But soon, the conversation would turn to Fatima.

Fatima’s death was harder to pin on her. She was a seven-year-old child wearing her uniform at school, so the usual victim blamers could not fault her for how she was dressed or speculate about whether she was drunk. Instead, they went for the next woman. People blamed her mother for not picking her up on time, as if a child could not be expected to wait outside her school without being brutally murdered.

But what else can we expect from a country which, along with Brazil, tops the list for femicides in absolute numbers in Latin America? We have a president who, after the news of these two murders broke, said he did not want to focus too much on the issue of femicides because it was being exaggerated to damage his mandate.

As if Mexico has not been known as the country of Las Muertas de Juarez (The Dead Women of Juarez) since 1993, in reference to the northern city of Ciudad Juarez, on the border with El Paso, Texas, where hundreds of women and girls were found dead by the side of the road showing evidence of torture, rape and strangulation.

Femicides continue in Juarez – most recently with the killing of 26-year-old Isabel Cabanillas de la Torre on January 18, triggering protests there last weekend by women demanding justice.

After decades of these hate-fuelled murders, women in Mexico are finally fed up with living in fear under a criminal justice system that lets murderers and rapists roam free; indeed, statistics from the National Human Rights Commission in Mexico show that around 90 percent of femicides in the country go unpunished.

The women of Mexico have found a way to push back against the lack of empathy for our plight: Sorority.

There has been an outcry from women banding together around the country, calling for better policies and systems to allow women to leave abusive relationships and for the abusers to be charged. Hundreds of thousands of women have taken to the streets to march for their rights under the hashtags of #NiUnaMenos (#NotOneLessWoman), #JusticiaParaIngrid (#JusticeForIngrid) and #IngridEscamilla.

Marches took place in 11 cities, including Mexico City, Monterrey, Guadalajara and Ciudad Juarez, on February 14 and 15 in honour of Ingrid.

Sorority has been found in unexpected places. Ingrid’s Twitter account shows that she actually shared anti-feminist content; however, as soon as her case was known, women organised marches all over the country in her honour.

Disgusted with the publication of gratuitous images of Ingrid’s mutilated body in the press, feminists all over Mexico uploaded pictures of beautiful landscapes with Ingrid’s name, so when people searched for her name online they would find those instead of the pictures of her body.

Even if some women feel the feminist movement “doesn’t represent them”, feminists will continue to fight for their rights.

Nevertheless, there remains a great deal of criticism aimed at feminist marches, from both men and women, including complaints about march sites being left covered in graffiti and some monuments being damaged.

Detractors say this is not a “proper way to protest”. Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, for instance, told feminists: “I understand you very well, but protest without violence.”

His wife, First Lady Beatriz Gutierrez, a journalist and writer, also chimed in, saying that there was no excuse for damaging historical heritage. She condemned a planned strike by women, using the hashtag #NoAlParoNacional (No To The National Strike). Gutierrez called instead for a “rally” in support of both women and her husband’s presidency.

The message here is “women, be quiet”. We even have a saying in Mexico that translates to “You look more beautiful in silence”.

People stand up for their precious statues and buildings but ignore the reason these women are taking to the streets in the first place. If only they cared for women as much as they do for statues – maybe the marches would stop.

There have been calls for the creation of Ley Ingrid (Ingrid’s Law), first proposed by the attorney general for justice in Mexico City, Ernestina Godoy, which would carry sanctions for public servants who leak images from open police investigations. This is in its early proposal stages at the Mexican City Congress.

Regardless of the outcome of this proposal, women are continuing to mobilise in Mexico in protest against the continued killings.

Women work on painting the names of more than 3,000 victims of femicide on Mexico City’s main plaza, The Zocalo, on International Women’s Day, March 8, 2020.

Right now, women’s groups are inviting all Mexican women to join the #UnDiaSinNosotras (#ADayWithoutUs) national strike, which will take place on March 9.

For this protest, women are being called on to disconnect from the internet and to refuse to go out, including to work or school.

Maybe our silence will be heard more loudly than our protests.

The Mother’s Blue Diamond Energy of Hope for Balance

I invoke the Mother/Father One,

the Mighty Ones, our Star Family,

the Divine Blessings, Virtues, Qualities,

Universal Laws, the dimensional growth patterns

for the ELIMINATION of gender violence ON GAIA

for HOPE, PEACE, LOVE, JOY – for BALANCE.

THE SCALES OF JUSTICE, OF WORTH AND OF THE UNIVERSE, IN BALANCE