With humanity facing the catastrophic consequences of a heating climate and plummeting biodiversity, experts say this is the decade to act [File: Bob Strong/Reuters]

By Jack Losh, Aljazeera, June 22, 2021

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/22/legal-experts-unveil-new-definition-ecocide

After six months of deliberation, a team of international lawyers has unveiled a new legal definition of “ecocide” that, if adopted, would put environmental destruction on a par with war crimes – paving the way for the prosecution of world leaders and corporate chiefs for the worst attacks on nature.

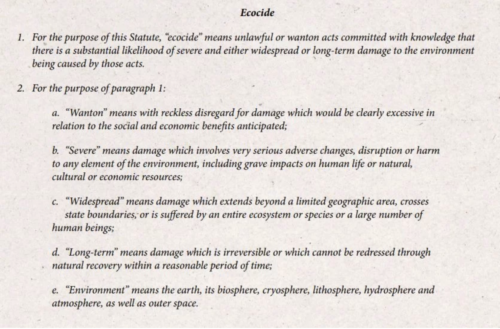

The expert panel published the core text of the proposed law on Tuesday, outlining ecocide as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts”.

Its authors want the members of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to endorse it and hold big polluters to account in a bid to halt the unbridled destruction of the world’s ecosystems.

“It is a question of survival for our planet,” said Dior Fall Sow, a UN jurist and former prosecutor who co-chaired the panel.

The draft legislation requires an ecocidal act to involve “reckless disregard” that leads to “serious adverse changes, disruption or harm to any element of the environment”.

Another section says such damage would “extend beyond a limited geographic area, cross state boundaries, or [be] suffered by an entire ecosystem or species or a large number of human beings”.

This environmental effect would either be “irreversible” or could not be fixed naturally “within a reasonable period of time”.

Finally, in order for ecocide suspects to be tried, the proposed law says the crime could be committed anywhere — from the Earth’s biosphere to outer space.

“This is an historic moment,” said Jojo Mehta, chair of the Stop Ecocide Foundation which commissioned the task force of international lawyers. “This expert panel came together in direct response to a growing political appetite for real answers to the climate and ecological crisis.”

‘Never too late’

Publishing the law’s core text is just the first step.

Any of the ICC’s 123 member states can now propose it as an amendment to the court’s charter, known as the Rome Statute.

Once that happens, the court’s annual assembly will hold a vote on whether the amendment can be considered for future enactment.

If this passes, member states must then secure a two-thirds majority to adopt the draft law into the Rome Statute, before each member could then ratify and enforce it in their own national jurisdiction.

At that point, ecocide would join genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression as the so-called “fifth crime” that could be prosecuted at the ICC.

Mehta hopes this could be achieved within four to five years. “This is the decisive decade for taking action,” she said.

“It is never too late. We still have nine years left of this decade. That’s plenty of time to act.”

In hammering out the law’s definition, the panel of 12 renowned lawyers from countries such as Bangladesh, Chile, Norway, Samoa, Senegal and the United States have sought a balance “between wanting to go far and wanting to be pragmatic”, said Professor Philippe Sands, the panel’s co-chair.

“We wanted to come up with a text that states could conceivably live with, and the initial reaction from those states we have shared it with has been immensely positive,” added Sands, who teaches law at University College London. “We’ve come up with a definition which we think could work but ultimately it will be for states to decide. And that is a matter of political will.”

At the moment, corporations that cause ecological devastation through deforestation, mining, oil drilling or other industrial-scale ventures typically only face financial penalties, leaving chief executives and other powerful decision-makers immune to criminal prosecution.

The ecocide campaign challenges that, threatening to rank them among war criminals and thereby providing a potent deterrent.

“[People who commit genocide] are not so bothered about their PR as a CEO,” said Mehta. “Corporate credibility, investor confidence, share price and so on depend very heavily on reputation. So a key decision-maker in a company being thought of alongside war criminals is not appealing at all.”

While the draft law’s adoption is not guaranteed, its publication nevertheless marks a considerable milestone in the fight to criminalise the worst ecological offences and place them alongside atrocities of international standing.

The campaign’s origins stretch back to 1970 when a botanist in the US first used “ecocide” to describe the nightmarish effect of the US military’s decision to release powerful, defoliating herbicides such as Agent Orange on forests during the Vietnam War, leading to cancers, birth defects and environmental ruin. Since then, high-profile figures such as Pope Francis and Greta Thunberg, as well as political leaders in Belgium, Finland, France and Luxembourg, have begun calling for ecocide to be recognised as an international crime.

The expert panel behind this new draft law was created in late 2020, 75 years after “genocide” and “crimes against humanity” were used to prosecute Nazi leaders at the Nuremberg Trials.

Its members hope that its publication could mark a similarly groundbreaking shift in justice and accountability, just as humanity faces the catastrophic consequences of plummeting biodiversity and a heating climate.

“In international law you get occasional moments where remarkable things happen,” said Sands. “I wonder if this might be such a moment.”

The Pink Pearl

Kwan Yin, through Linda Dillon,

channel for the Council of Love:

Insert this pearl into

the heart of nations, oceans,

rivers, streams, hurricanes, tornadoes,

mountains, and into every City of Light.

Carry them in a bag so that you are never running short.

It is a beautiful peridot bag that is my vibration and colour.

It is the gentle, tender Love. . . .

Kwan Yin, Goddess of Compassion and Mercy, on Sending Love

How 165 Words Could Make

Mass Environmental Destruction

An International Crime

The draft defines ecocide as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.”

Charlie Riedel/AP

By Josie Fischels, NPR, June 27, 2021

Mass environmental destruction, known as ecocide, would become an international crime similar to genocide and war crimes under a proposed new legal definition.

The definition’s unveiling last week by a panel of 12 lawyers from around the world marks a big first step in the global campaign’s efforts to prevent future environmental disasters like the deforestation of the Amazon or actions that contribute to climate change.

There are currently four core international crimes: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression.

These crimes are dealt with by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide spent six months preparing the 165-word definition, working with outside experts along the way. In a draft of the definition by the Stop Ecocide Foundation, a Netherlands-based coalition, panelists said they hoped the proposed definition could provide a basis for the consideration of a new international crime.

So, what’s the proposed definition?

The draft defines ecocide as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.”

Proposed definition of ecocide.

Stop Ecocide Foundation/Screenshot by NPR

Unlike the existing four international crimes, ecocide would be the only crime in which human harm is not a prerequisite for prosecution.

“There are elements of human harm that can be included in (the definition), but it also extends to damage, per se, to ecosystems,” said Jojo Mehta, chair and co-founder of the Stop Ecocide Foundation.

“So effectively you’re looking at something that has, at least in part, potential to be a crime against nature, not just a crime against people.”

The original ecocide proposal is almost 50 years old

The intent to make ecocide an international crime isn’t new. The idea was brought up by then-Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme at the 1972 U.N. Conference on the Human Environment.

In his speech, he warned that rapid industrial progress could deplete natural resources at unsustainable levels.

But even before that biologist and bioethicist Arthur Galston used the word “ecocide” at the 1970 Conference on War and National Responsibility in Washington, D.C.

Several other attempts at formalizing ecocide as an international crime have emerged since then.

Ecocide was considered and then dropped during the formal establishment of the ICC in 1998.

For 10 years until her death in 2019, Scottish barrister Polly Higgins campaigned for ecocide to be recognized as a crime against humanity.

The Stop Ecocide Foundation took up the challenge in 2017.

A proposed definition is just the start of a long process

What would it take for the ICC to adopt the ecocide definition and amend the Rome Statute? A lot.

Here are the steps that would need to happen:

One of the International Criminal Court’s 123-member countries (which do not include the U.S., China or India) would have to submit a definition to the United Nations secretary-general

The proposal must then be voted on by a majority of members of the ICC at the annual assembly in December in order to be considered.

Once the final text for an amendment is discussed and agreed upon, two-thirds of member countries must vote in favor.

The vote is ratified and must be enforced in countries a year later. While it will become a criminal offense in the countries where it is ratified, ratifying nations may arrest non-nationals on their own soil for ecocide crimes committed elsewhere. This means citizens of countries that are not members of the ICC could still be affected.

Between the formal proposal of an ecocide crime by a member country and ratification, however, an amendment process could take years to decades. The court would hold a vote at their annual meeting in December to take up the proposal, and after that, debates would begin to finalize the crime’s definition.

Despite this, Mehta says that rapidly growing conversations and support around the subject have given the panel confidence.

“We don’t see any likelihood of it disappearing. The likelihood is it will actually get proposed,” she said. “However, even if it takes longer than we would like … just the fact that this conversation is happening is already making a difference.”

The International Crime Court has not yet commented on the panel’s proposal.