jackie sumell, Photo by Maiwenn Raoult

Volunteers team up with people currently held in solitary confinement to build empathy, compassion, and advocacy for a world without prisons.

By Roshan Abraham, Yes Magazine, July 2, 2021

In a small patch of green space on Andry Street in New Orleans’ lower ninth ward, nine garden beds lie next to one another, each 6 feet by 9 feet, each the size of one standard solitary-confinement cell.

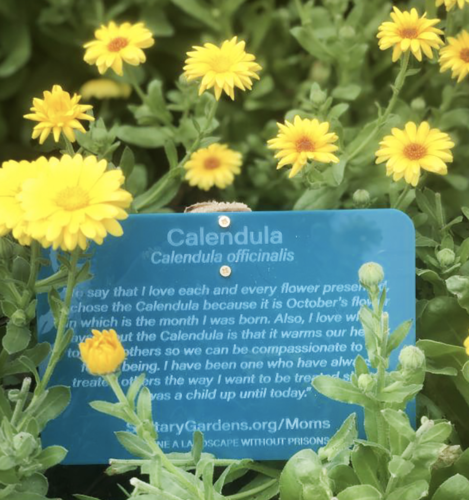

Each garden bed grows a mix of herbs and flowers, among them pansies, stinging nettles, onions, mugwort.

They are a mix of plants with medicinal properties and some that just bring pleasure to the eyes, and their growth is limited to the parts of the tiny space where a person would be free to move in a solitary cell, with space blocked off for where the furniture—nothing more than a bed and a toilet—would be.

The plants in each garden are chosen by someone in solitary confinement and planted by a volunteer gardener on the outside.

The result is both symbolic and produces plants with tangible uses, says jackie sumell (who does not capitalize her name), who conceived the project; plants with healing properties will be redistributed to people who need them through what sumell calls a “prisoner’s apothecary.”

The solitary beds are eventually overrun with plant life, a visual representation of a world without prisons, an idea that forms the project’s core mission.

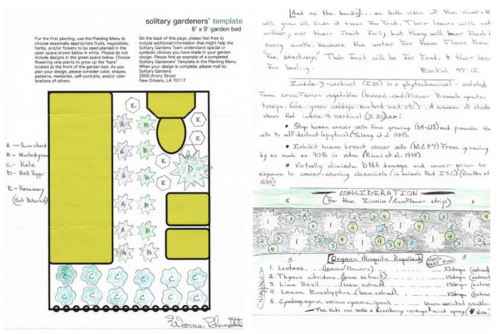

Typically, a volunteer gardener on the outside will send a list of plants to an incarcerated gardener.

The list provides plenty of options but is limited to what will thrive in the climate and season.

They collaborate on a gardening plan and a calendar, often with a small floor plan filled in by the incarcerated gardener laying out the positioning of plants.

Once plants get chosen, a plant bed is constructed from tobacco, cotton, and indigo grown on-site, which is mixed with lime, water, and clay, a concoction sumell calls “revolutionary mortar.”

Those plants were chosen because of their role in chattel slavery, meant to evoke the connection between the slave trade and the prison system.

Then the volunteer plants the incarcerated person’s chosen plants to the best of their ability.

Because the beds are only 6 by 9, sometimes not all the plants will fit, and they’ll have to wait until they’ve harvested what they now have.

A volunteer at one of the solitary garden plots. Photo from jackie sumell.

Many choose plants with healing properties. sumell says one gardener is interested in adaptogens, plants like ginseng and holy basil that are believed to reduce stress levels, and which sumell says can help with internalized trauma.

“Their garden was specifically designed thinking about ways that would have prevented getting them in prison to begin with,” sumell says.

The idea behind the gardens began through a dozen-year-long collaboration between sumell and Herman Wallace, who, along with Albert Woodfox and Robert King is one of the “Angola Three,” former Black Panthers who served decades in solitary confinement at Louisiana State Penitentiary and whose convictions were later overturned.

Their conversations and sumell’s quest to imagine a home where Wallace could return home from prison led to an art project called “The House That Herman Built,” also the subject of a documentary.

In Solitary Confinement For A Crime He Didn’t Commit,

Herman Wallace Built His Dream House

“What kind of house does a man who lives

in a 6-foot-by-9-foot cell for 30 years dream of?”

Wallace was released from prison Oct. 1, 2013, and died from liver cancer three days later.

sumell began the solitary gardens project to continue his legacy, inviting Albert Woodfox, who was released in 2016, to be one of the inaugural gardeners.

The garden has been funded through grants from about a dozen organizations over the years, and now gets most funding from the New York-based nonprofits Creative Capital and Art For Justice, but it relies heavily on the support of dedicated volunteers.

Christin Wagner, a volunteer who has lived in New Orleans for nine years, is partnered with an incarcerated gardener named Jesse, who is being held at ADX Florence, a maximum security federal prison in Colorado.

Solitary Gardens requested that Jesse’s last name not be used for fear of retaliation from prison officials.

One of the garden plans created by a solitary gardener. Photo from jackie sumell.

Jesse’s requests were for plants that people could find useful, according to Wagner.

“He likes the idea that it can come from the ground and nourish someone,” Wagner says.

Jesse also asks for pansies, for the color and because his mother loves the plant.

Wagner’s letter writing with Jesse led her to develop a friendship with Jesse’s wife, who along with Jesse’s mother, aunt, and cousins visited the garden he had planned from prison.

It was really, really, incredible, it was very heavy too,” Wagner says.

“None of us at the garden have ever met Jesse, but we feel he’s part of our extended family.”

Two solitary gardeners were recently released from prison and now volunteer in person.

Ricky Teano, 30, was incarcerated for 10 years and released in January.

Teano says he’s served a few stints in solitary, with the longest being two weeks.

He got involved with the garden from prison about 18 months ago when an incarcerated mentor—who also has a garden bed at Andry Street—connected him with sumell.

“It was a way of healing the bridge between me being incarcerated and individuals in society,” Teano says.

“When I grew up, my dad was big on old school remedies and stuff,” he says.

This led him to choose plants with healing or medicinal properties, including mint and sage.

Since his release, he says volunteering with the garden has helped him transition into society.

“It’s a form of therapy for me,” he says.

Photo from jackie sumell.

The concept of solitary gardens have been reproduced across the country, including garden beds in Philadelphia and Texas.

“The solitary gardens are open source and totally replicable,” sumell says.

She is not involved in all the gardens, but does help with some, including a garden grown in collaboration with UC Santa Cruz’s arts department.

This garden bed is curated by Tim Young, who is incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison.

Young answered questions over the phone via an intermediary, because San Quentin limits his phone contacts to a pre-approved list.

“I think it was a matter of the stars and the universe coming into perfect alignment,” Young says about connecting with sumell and the gardens.

Young had seen sumell in the “Herman’s House” documentary in 2012 and wrote her letters for years, he said, not receiving a response.

In 2019, he received a letter asking him to participate in the solitary gardens project, to which he replied yes.

Two months later, sumell visited him in San Quentin and asked him to be the solitary gardener for UC Santa Cruz.

“I think it’s a crime to encase people in concrete cages and deprive them of nature,” Young said.

“What the garden has done is give me a greater appreciation of all the things that I am no longer able to feel, touch, or enjoy. I haven’t touched the earth or leaned upon a tree in over 22 years,” he said from prison.

Young wanted plants that could heal the body and mind, he said, and chose mugwort as well as a favorite, stinging nettles.

Eventually, these bars will be covered by greenery. Photo by Maiwenn Raoult.

Young has received letters over the years from people visiting the garden, including students and their parents on campus tours.

“Many of them wrote about how it had changed their lives, it had served as an epiphany for them,” he said.

“To my surprise, much more has sprouted up than plants and herbs,” Young said of his experience with the project.

“There have been friendships and alliances and collaborations and, you know, general support.”

sumell wants to create a more permanent space in New Orleans to host the prisoner’s apothecary, and hopes to eventually provide jobs with living wages to formerly incarcerated people working at the gardens.

This story was originally published by Next City, and appears here as part of the SoJo Exchange from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems

What Does Accountability Look Like

Without Punishment?