In the teachings of the Blessing and Virtue of Hope, Universal Mother Mary, through Linda Dillon, channel for the Council of Love, said we are not to stand for children being shot, families going hungry, and inequality because none of these things are of love:

In the teachings of the Blessing and Virtue of Hope, Universal Mother Mary, through Linda Dillon, channel for the Council of Love, said we are not to stand for children being shot, families going hungry, and inequality because none of these things are of love:

“Violence against women has been the disgrace of our planet beginning with Gaia who has been terribly abused.

“Sexual violence, predatory violence, physical violence — we cannot have whole productive communities, productive, loving families — and have women that are being suppressed, mutilated, killed, beaten, because they are women.”

I just finished reading Highway of Tears by Jessica McDiarmid.

I just finished reading Highway of Tears by Jessica McDiarmid.

This is the overview on the dust cover:

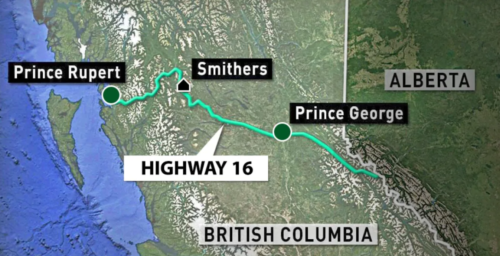

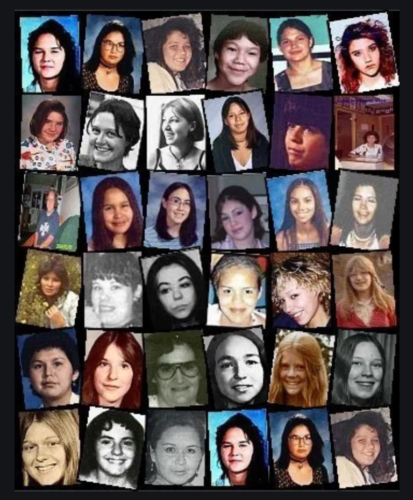

For decades, Indigenous women and girls have gone missing or have been found murdered, along an isolated stretch of highway in northwestern British Columbia.

The highway is known as the Highway of Tears and it has come to symbolize a national crisis.

Journalist Jessica McDiarmid investigates the devastating effect these tragedies have had on the families of the victims and their communities, and how systemic racism and indifference have created a climate where Indigenous women and girls are over-policed, yet under-protected.

Through interviews with those closest to the victims — mothers and fathers, siblings and friends — McDiarmid offers an intimate, first-hand account of their loss and relentless fight for justice.

Examining the historically-fraught social and cultural tensions between settlers and Indigenous peoples in the region, McDiarmid links these cases to others across Canada — now estimated to number up to 4,000 — contextualizing them within a broader examination of the undervaluing of Indigenous lives in this country.

Highway of Tears is a powerful story about our ongoing failure to provide justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, a testament to their families and communities’ unwavering determination to find it.

On page 146, Canada’s Indian Act is described and how Indigenous women used to be treated in their own societies:

The Indian Act, and the wider forces of colonization, took particular aim at women. “It was absolutely part of a larger project to assimilate and eliminate,” said Dawn Lavell-Harvard, former president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada, “but also just completely reflective of a misogynistic, patriarchal world view. Women were property.”

In most Indigenous societies, men and women played complementary roles that were seen as equally valuable.

Indigenous women were independent and powerful, with control over their property, sexuality, marital choices, and resources. They were leaders in their communities, responsible for major decisions.

They were revered and respected as the givers of life.

The prevailing view of women is reflected in the oft-quoted Cheyenne proverb: “A nation is not conquered until the hearts of its women are on the ground. Then it is done, no matter how brave its warriors or strong its weapons.”

Unfortunately, the poor treatment of our Indigenous sisters and brothers in Canada is now reflected in our child welfare system, as it says on page 229:

There are now more Indigenous children in the child welfare system than at the height of residential schools, in fact, the system has been called, “a second generation of residential schools.”

Mothers of children in care are more likely to die young. A study published in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry in 2017 showed they have a suicide rate four times higher than mothers who maintained custody of their children.

The study attributed this partly to “feelings of guilt, responsibility, shame, stigmatization, and loss of self-worth [that] are often associated with this type of custody loss.”

Over the years, many recommendations were put forth to stop the murder on the Highway of Tears.

One of them was a shuttle service (proposed in 2006) so there was no need to hitchhike. This was implemented in 2017.

Many Indigenous women have led Walks along the Highway of Tears to bring awareness and change. Gladys Radek, aunt of Tamara Chipman (one of the girls who went missing) said:

“When you’re walking on those highways, you feel the spirits of those women.”

“In our canoe, we pray for everyone but ourselves,

so those who need it can hear our prayer.”

~ Coast Salish tradition ~

The US Department of Justice found that American Indian women

face murder rates more than 10 time the national average.

4 out of 5 of our Native women are affected by violence today.

And to close this long post, some good news, April 7th, 2021:

‘From Prince George to Prince Rupert’:

Highway of Tears to get full cellular connectivity

Cellular connectivity along the highway

is key for the safety of Indigenous women and girls.

The Mother’s Blue Diamond Energy of Hope for Balance Everywhere