A roundup of articles on the status of the Coronavirus and ways we can help….

A roundup of articles on the status of the Coronavirus and ways we can help….

Seattle a ghost town? Thanks to Tom.

COVID-19 requires gender-equal responses to save economies

Isabelle Durant, Deputy Secretary-General, and Pamela Coke-Hamilton, Director, Division on International

InterPress Service, April 2, 2020

http://www.ipsnews.net/2020/04/covid-19-requires-gender-equal-responses-save-economies/

– Globally, women are more vulnerable to economic shocks wrought by crises such as the coronavirus pandemic.

Why are women so at risk?

Firstly, women are more likely to lose their jobs than men. In many countries, women’s participation in the labour market is often in the form of temporary employment.

Across the world, women represent less than 40% of total employment but make up 57% of those working on a part-time basis, according to the International Labor Organization.

As the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic roll through economies, reducing employment opportunities and triggering layoffs, temporary workers, the majority of whom are women, are expected to bear the heaviest brunt of job losses.

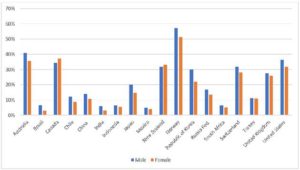

Source: ILOStat – Percentage of respondents who report borrowing any money in the previous 12 months (by themselves or together with someone else) to start, operate, or expand a farm or business (% age 15+).

Safety nets not wide enough

Many women will not be rescued by social safety nets. as access to safety nets frequently depends upon a formal participation in the labour force.

But since women tend to work without clear terms of employment, they often are not entitled to reliable social protection such as health insurance, paid sick and maternity leave, pensions and unemployment benefits.

In many developing countries, women are either self-employed or work as contributing family workers, for example in family farms.

In South Asia, over 80% of women in non-agricultural jobs are in informal employment; in sub-Saharan Africa this figure is 74%; and in Latin America and the Caribbean, 54%of women in non-agricultural jobs participate in informal employment.

Service sector reeling under restrictions

The service sector is being hit hard by the restrictions imposed to manage the spread of the coronavirus.

Given that some 55% of women are employed in the service sector (in comparison with 44% of men), women are more likely to be adversely affected.

Moreover, female-dominated service sectors such as food, hospitality and tourism are among those expected to feel the harshest economic effects of the measures to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Limited access to credit

Women entrepreneurs are often discriminated against when attempting to access credit. This will be a challenge as credit will be of paramount importance in the survival of firms.

Without open and favourable lines of credit, many female entrepreneurs will be forced to close their businesses.

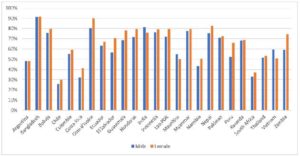

Source: ILOStat. Part time employment refers to regular employment in which working time is substantially less than normal

More work, no pay

Women’s unpaid work is set to increase. Women remain responsible for the lion’s share of domestic chores and care work.

Measures to contain the pandemic such as quarantines and closures of schools imply additional household work and responsibility.

Some women may be forced to make difficult decisions to leave the labour market or opt for part-time jobs, as juggling between caring for family members and paid work becomes untenable.

Safeguard gender progress

As governments take steps to address the economic and social effects of COVID-19, they should not let it reverse the gender equality progress achieved in recent decades.

To avoid this, we must retain women’s productive participation in the labour force. Something we did not do in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. Here support measures were provided to large infrastructure projects that mainly employed men, while jobs were cut in teaching, nursing and in public services, all female-intensive sectors.

Support measures in response to COVID-19 should go beyond workers who hold formal employment and include informal, part-time and seasonal workers, most of whom are women.

This is particularly necessary in female-dominated spheres such as the hospitality, food and tourism sectors, now at a standstill due to confinement measures by governments.

Some countries are already moving in this direction. For example, Italy is considering putting into place support measures to cover informal and temporary workers once their contracts are over.

Government bailouts and support measures should not only prop up large and medium-sized enterprises, but also micro- and small businesses, where women entrepreneurs are relatively more represented.

In addition, private sector financial support and access to credit should be equally available to women and men.

More transparency and a simplification of public procurement processes would also help women’s businesses to benefit from increased government support.

The reallocation of public funds should avoid any possible increase in the burden of women as principal suppliers of unpaid work.

Create a gender-equal future

The coronavirus pandemic presents us with an opportunity to effect systemic changes that could protect women from bearing the heaviest brunt of shocks like these in the future.

Improved education and training opportunities for women would facilitate the shift from precarious jobs to more stable and better-protected employment.

Gender-responsive trade policies would open new opportunities to women as employees and entrepreneurs.

Broader provision of social services would lift women’s care burden and give them more time for paid jobs and leisure.

Flexible work arrangements, currently in place in response to the pandemic, should continue beyond it and provide a new model of shared responsibilities within households.

Our ability to bounce back from this crisis is dependent on how we include everyone equally. If more women take part in shaping a new social and economic order, chances are that it will be more responsive to everyone’s needs and make us all more resilient to future shocks.

Five Questions to philosopher Philippe Van Parijs on basic income and the coronavirus

Five Questions to philosopher Philippe Van Parijs on basic income and the coronavirus

Dozens of members of the British Parliament signed a letter pleading for an “Emergency Universal Basic income”. In order to deal with the economic and social impact of the COVID 19 crisis, many more around the world, from Italy to India, are now advocating the introduction of an unconditional basic income.

You have been defending that idea since the early 1980s. In 1986, you convened in the university town of Louvain-la-Neuve the first international conference on basic income, which saw the birth of BIEN, a network that now spans the whole world (basicincome.org). And you recently published a reference book on the subject (Philippe Van Parijs & Yannick Vanderborght, Basic Income. A radical proposal for a free society and a sane economy, Harvard University Press, 2017) already translated into several languages, including Chinese and Korean. Has its hour finally come?

In these forty years, I have learned not to get excited too quickly. It is true that the idea is coming up right, left and centre. But there are several versions, with distinct purposes.

One purpose is to ensure that no one ends up with no income for weeks on end as a result of the lockdown imposed by a government.

In many countries, including Belgium, some scheme of “technical” or “temporary” unemployment is triggered, with workers receiving a benefit worth 70 or 80 percent of their wage for a limited period of time. But it is harder to design a scheme that covers satisfactorily the growing category of the self-employed, the platform workers and workers with irregular or “zero-hour” contracts.

In several countries, these are the categories that have been growing fastest in recent years. This is what inspired the British proposal you mentioned. At the end of March, over 170 members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords advocated the introduction of an “Emergency Universal Basic Income” for the duration of the pandemic: an amount equivalent to the after-tax living wage, to be paid weekly to all residents and funded by public borrowing.

Compared to the existing schemes, including the UK’s so-called “universal credit”, such a genuinely universal scheme would have the advantage of reaching all households with a minimal amount of bureaucracy.

But it would have the disadvantage of increasing at a high cost the net income of a majority of people whose problem is not that they have too low an income, but that they cannot spend it due to shop closures.

It can therefore be argued that the public debt would be unnecessarily swollen by such a measure, and that something more finely tuned to address the sudden fall in income of the people hit by the crisis would make more sense, even if the targeting is imperfect.

Is an “emergency basic income” different from so called “helicopter money”, a label sometimes also used to defend a universal basic income?

The purpose is different. When an economy is in a recession, a central bank will want to boost it by pumping more money into it. This is commonly called “Quantitative Easing” and usually achieved by enabling and inducing private banks to lend more to both firms and households.

But as interest rates approached the lowest possible level, many economists started pleading for so-called “Quantitative Easing for the People”, the “printing” of money to be distributed directly to households.

The simplest way of doing so consists of a direct payment of the same amount into the bank account of every resident. Of course, such a payment has an inflationary effect, and it is meant to have one. It is to be used when there is not enough inflation, and it must therefore necessarily be temporary, which is also the case for an emergency basic income or other measures meant to address the immediate impact of the pandemic on the disposable incomes of many households.

But its optimal timing is different. Helicopter money is best reserved for the moment businesses can reopen and will welcome a strong demand.

The fear sometimes expressed is that, just as firms may not invest even when interest rates are very low, households may not spend but rather hoard the additional income they receive.

Some of the proposals for a “QE for the people” therefore propose that this payment should be made in a “melting” currency that loses value through time, so that households would be encouraged to use it straight away.

Some of the proposals also exclude households with high incomes and therefore a lower propensity to consume. As well explained in a recent paper by the NGO Positive Money, the European Central Bank would be well advised to adopt some version of this “QE for the people” as soon as the confinement measures can be relaxed in the Eurozone.

How does Trump’s “universal basic income” of 1200 dollars fit into this distinction between two distinct purposes?

The bill that was passed in March by the US Congress promises the one-off payment of an unconditional grant of 1200 dollars to all residents with an annual gross household income of less than 90.000 dollars.

In addition to the wish to be generous in an election year, both purposes are relevant here: buffering the immediate income loss of many and boosting aggregate demand for the whole economy.

But from what I read, the administrative challenge of reaching many of those who most need the buffer is such that it will take several weeks before they get their 1200 dollars.

As to the macroeconomic stimulus, it will presumably work in the parts of the country least affected by the crisis but will hit against the lockdown in those most affected.

You seem rather lukewarm about these various developments.

The measures proposed or about to be implemented serve useful purposes and, in certain circumstances, they can provide the best tool available. But they are all intrinsically temporary.

Over more than the short term, they are unsustainable. However, they all share a most welcome virtue. They all boost our awareness of how much better equipped our societies and our economies would be to face challenges such as this one if a permanent unconditional basic income were in place.

Had this been the case, there would be no people left with no income at all, waiting for ad hoc schemes to be implemented or trying to find out how they could access existing schemes they never dreamt of ever needing.

Contrary to an emergency basic income, a permanent basic income would not boost the net income of the rich nor need to be funded by a massive increase in public borrowing. The bulk of it would be paid for by those whose income is not affected by the crisis.

This would not make it unnecessary to have social insurance schemes that protect both wage earners and the self-employed against a sudden income loss. But such schemes would come on top of a basic income security provided unconditionally to all.

If such a basic income existed at EU level, it would in addition operate as automatic solidarity between member states, with the shock attenuated in the countries hit hardest.

Moreover, whenever Quantitative Easing would be required, the pipeline would be ready for it, in the form of an administratively straightforward temporary increase of the basic income regularly paid to all.

So, do you think that the time is ripe for a fundamental reform of our social protection systems that would incorporate such a permanent basic income, even possibly at the European level?

I believe in opportunistic utopianism. Crises can provide opportunities for major breakthroughs.

In Belgium, universal male suffrage was the product of World Wart I, and a developed welfare state, like in many other countries, the product of World War II.

We do not know at this stage how long, how deep and how wide the economic crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic will be. But we must try to use the momentum to restructure our institutions so as to make our economies and our societies more fair and more resilient.

After the Swiss referendum and the Finnish experiment, the presidential campaigns of Benoit Hamon in France and Andrew Yang in the United States the many proposals for an “Emergency Universal Basic Income” or for a “QE for the people” in response to the current crisis can further contribute to persuading people that an unconditional basic income is a central part of what we need.

To make it a reality in a particular national context or at the European level, visionaries and activists are needed, but also, at the right moment, clever institutional tinkerers and courageous politicians.

Universal Basic Income in battle against COVID?

Universal Basic Income in battle against COVID?

Greg Price, Vauxhall Advance, April 2, 2020

Several countries have tinkered with the idea of Universal Basic Income (UBI).

A platform foundation for the Alberta Liberal Party back in the 2019 election, for party leader David Khan, the time for a temporary UBI during the COVID-19 pandemic is now.

“It’s been a patchwork of different programs at different levels of government. Things are changing every single day and every week. For example, the federal government announced two COVID-related benefits last week, then merged them into one benefit (the next) week,” said Khan, adding a UBI would streamline the process of giving families financial security during the COVID-19 pandemic that has brought the North American economy to a near stand still.

The Alberta Liberals are calling on the federal government to implement a temporary Universal Basic Income of $1,500 per month per Canadian adult and $500 per child. The UBI should not be means tested, given the current COVID-19 situation past earnings may not reliably indicate who needs fiscal support.

Khan, a trained lawyer, runs an immigrant services agency. With employers working from home in self isolation and taking calls, those calls have taken on a familiar theme.

“All the calls we are getting from our clients, regardless of what programs and services they were getting before, was ‘how do we apply for these programs? Who qualifies, who doesn’t?’ It’s head spinning even for someone like me who has legal training and has been around politics a long time and has analyzed policy. It’s difficult to figure out,” said Khan.

“The federal government is trying to adapt and tinker with existing EI programs and application processes. There’s portals they are tacking on different benefits, and changing them with who is eligible and who isn’t. It’s almost impossible for the general public to understand what they qualify for, where they should apply and whether the benefit kicks in while they wait for the EI. More critically, the government just does not have the man power and technological resources to handle all these online claims.”

He cited the Alberta Emergency Benefits website crashing.

“There’s a federal benefit that is supposed to be coming in 10 days or so, I don’t think it’s going to come that quick. And the EI is going to be incredibly delayed,” said Khan. “They had a million people apply (the March 15) week and had to process 140,000 applications. It’s going to take a lot longer for this money to get out to people and I think it’s going to cause a lot of social dislocation with people falling through the cracks and becoming desperate.”

While the Alberta Liberal Party would like to see UBI be a permanent fixture, it’s especially needed in the unprecedented time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“They could do Universal Basic Income in a couple of days. Ninety per cent of people file tax returns and most of those have direct deposits set up with the CRA. Fire out this benefit and get this into their accounts right away. We can figure out next year, the 2021 tax year, who needed it and and who didn’t and tax it back from those who ended up getting it who didn’t need it,” said Khan.

“That’s 90 per cent of people not needing to flood government application websites with unnecessary application.”

Different countries have dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic with different levels of efficiency, but mounds of red tape in social assistance programs is clogging things up.

In the moment of the COVID-19 crisis for Khan, now is not the time for incrementalism, but rather bold moves in showing leadership in supporting the economy and individuals.

“Had we had a UBI in place, up and running already, it could have been easily tweaked increasing payments for the time being and would have been automatic,” said Khan. “In the long run, UBI could replace many social service programs that provide income to those who need it. The associated bureaucracies could be eliminated where there could be huge cost savings in administrative costs in rolling everything into a permanent UBI. Other savings could come from reduced social costs and other social ills that are caused by people not having a basic income or not being able to access the myriad of complicated overlapping and different-level government programs out there.”

Khan gave a tip of the hat to premier Jason Kenney, prime minister Justin Trudeau and the medical health officers for their availability and being upfront in transparency in giving daily press conferences in keeping the public informed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Residents and staff wave to family and friends who came out to show support of those in the McKenzie Towne Long Term Care Centre, where there are 35 confirmed COVID-19 cases, in Calgary, Alta., on April 2, 2020. Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

Care homes across Canada desperate for staff amid COVID-19 outbreak turn to librarians, museum workers

Kelly GrantHealth reporter and Laura Stone, Queen’s Park Reporter, Globe and Mail, April 2, 2020

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-care-homes-across-canada-desperate-for-staff-amid-covid-19-outbreak/

In Ontario’s Bruce County, librarians are being asked to trade checking out books for checking temperatures at the doors of nursing homes.

The county located along the shore of Lake Huron has offered library and museum workers the opportunity to keep earning their full salaries during the pandemic shutdown if they are willing to serve meals, clean bed pans and help residents with activities at two publicly owned long-term care homes.

Only seven of 54 workers have accepted the offer, even though COVID-19 has not been detected in either home.

Bruce County’s effort to turn librarians into nursing-home aides is just one example of the ways governments and the owners of long-term care and retirement facilities are scrambling to find extra staff as the new coronavirus sweeps through homes for seniors, sickening some front-line caregivers and frightening others away.

In Quebec, the provincial government announced $287-million in funding on Thursday to offer a $4-an-hour raise to personal support workers in seniors’ homes and bonuses to other front-line staff fighting the epidemic.

In British Columbia, the provincial health officer has taken control of staffing at nursing homes in the Vancouver area for six months to guarantee equal pay to workers and ensure they don’t split their time between multiple facilities.

‘It is a very dire situation’: At least 600 nursing, retirement homes in Canada have coronavirus cases

The latest on the coronavirus: Advocates say COVID-19 limiting access to contraceptives, abortion; Ontario to release modelling data

Calgary’s Chief Medical Officer tightens rules for staff at congregate-care facilities

There was a severe shortage of personal support workers – the aides who bathe, change and feed elderly residents – even before the coronavirus hit nursing homes, with some employers offering benefits for part-time staff or $1,000 retention bonuses to help attract workers to care for the country’s aging population.

Now the pandemic has intensified the staffing crisis, said Heather Maxwell, chief executive officer of Maxwell Management Group, a health-care recruitment firm trying to fill hundreds of openings in seniors’ facilities across the country.

“It’s been a challenge for a while, to be honest with you. [COVID-19] certainly has put an extra stresser on the system,” she said.

In Ontario, five groups representing long-term care and resident organizations released a joint letter this week warning the sector is facing the potential loss of half of its front-line work force during the pandemic.

Donna Duncan, CEO of the Ontario Long-Term Care Association, one of the letter’s signatories, said that the sector is struggling against fear.

“We’re getting suppliers who are dropping supplies off on the road,” said Ms. Duncan, whose group represents 70 per cent of Ontario’s 630 long-term care homes. “They won’t even come up the steps.”

Some homes can’t get plumbers or elevator repair people to complete work, she added.

The novel coronavirus has caused more devastation in nursing and retirement homes than in any other setting in Canada, with at least 75 deaths among residents as of Wednesday, according to a tally done by The Globe and Mail after contacting local and provincial public-health authorities across the country. The new coronavirus has invaded at least 600 nursing and retirement homes.

The toll continues to rise. Two more residents died of COVID-19 overnight on Wednesday at the Pinecrest Nursing Home in Bobcaygeon, Ont., the site of the deadliest outbreak in the country.

Ms. Duncan of the Ontario Long-Term Care Association said she supports the Ontario government’s recent emergency order that relaxes requirements around completing paperwork, and allows homes to hire and deploy staff where needed.

She said there is a labour force looking for work that could help in homes with general care – anyone from dental hygienists to housekeepers to food handlers.

Candace Rennick, secretary-treasurer of CUPE Ontario, said she understands the need to boost staffing in long-term care homes, but bringing in untrained workers or volunteers puts both staff and residents at risk.

“These people aren’t necessarily trained to deal with long-term care issues, they’re not trained to deal with infection-control issues,” she said. “Do we appreciate that there is a crisis and providers need relief? Absolutely, but those measures can’t come at the health and safety risk of the people who are living and caring for the residents.”

On Thursday, CUPE Ontario members in the long-term care sector wore stickers on the job to protest what they see as second-class treatment when it comes to their access to personal protective equipment.

“The most important thing first is that we make sure that all front-line health care workers in hospitals, home care and long-term care have the personal protective equipment that they need to remain safe and healthy,” she said.

In the case of Bruce County’s long-term care homes, Gateway Haven in Wiarton and Brucelea Haven in Walkerton, retaining staff has not been a problem, according to Jill Roote, the county’s emergency information officer.

The county’s offer to library and museum workers was simply an attempt to plan ahead, she said by e-mail. “In order to be pro-active under a health crisis, it is important to put measures in place to ensure the protection of the most vulnerable – our long-term care residents.”

With reports from Jill Mahoney and Les Perreaux