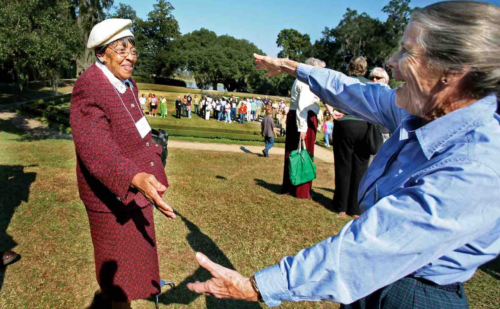

Group photo of guests at the 2006 reunion. Photo by SWNS.

Descendants of Slaves and Slave-Owners Are Bonding at South Carolina Plantation Where They Share Their Painful Past

Good News Network, November 16, 2018

The descendants of slaves and slave owners have been finding friendship, reconciliation, and wisdom by meeting with each other for weekend-long reunions at the South Carolina plantation where they share a painful past.

Every five years, the ancestors of slaves who toiled away at the Middleton Place plantation in Charleston, South Carolina gather together with the relatives of the plantation’s slave-owning family for a two-day stay.

SWNS

Together, the guests share meals, tour the house and gardens, and listen to lectures about their ancestors’ lives on the plantation.

Over 3,500 slaves worked on the Middleton family’s 19 plantations in South Carolina during the 18th and 19th centuries. The plantation is now a national historic landmark, home to the oldest landscape gardens in America and attracts around 120,000 tourists a year.

The first reunion was held in 2006 after an African-American plantation descendant proposed that the separate reunions held for white and black descendants should be united into one event. The second reunion took place in 2011 and the third in 2016 was attended by 300 descendants.

66-year-old Rose Morton, who is a retired post office worker, attended the first reunion after discovering that her ancestors had been enslaved at the plantation.

“When my mother died in 2000, that’s when I wanted to find family. I started doing research online, visiting the Alabama archives and looking up public records. I found out that we were from Middleton Place,” said Morton.

Morton’s great-grandfather Ceasar was born at Middleton Place in 1793. She said returning to Middleton Place and meeting with the descendants of those who enslaved her ancestors was an emotional experience.

“I could feel the earth move under my feet. I felt that they were there,” said the mother-of-two from Southfield, Michigan. “I thought I would be scared the first night, that I would have nightmares, but I slept like a baby.

“I would meet people and at first I was just a black person visiting, but after they knew I was a descendant, they would shake my hand as though they wanted to feel something.

“It felt so natural to me,” she added. “It was like I was at home.”

Guests at the reunion in 2016. Photo by SWNS.

She added that there were awkward moments during the reunion, but by the time she attended the third reunion in 2016, all her nerves were gone.

“At the first reunion, no one knew what to do,” she said. “We were on edge. The descendants of the slave owners had to carry that pain, but it wasn’t them. They don’t want to carry it, but they do.

“By the third reunion, we felt like: ‘what the heck?’ We were hugging each other,” continued Morton. “We accepted it as a family reunion.”

54-year-old Lee Pringle, who is a music festival organizer, has also attended the reunions since his great-great-grandfather, Isom Pringle, was a slave at Middleton Place.

Pringle is now a board member at Middleton Place where he helps the foundation interpret the plantation’s history from an African-American perspective.

“It is a magical thing,” Pringle said about the reunions. “It gives us the opportunity every five years to put things in check.

Guests at the reunion in 2016. Photo by SWNS.

“Friendships have developed and because of social media, we keep in touch,” he added. ”We have a sense of family and we refer to ourselves as ‘cousinry’.”

Thus far, there have been more descendants of slave owners than of slaves attending the gatherings—approximately 60% European to 40% African-American.

“I’ve always been intrigued by the interconnection of white and African-American history. Our history is so interwoven, although it’s so ugly that the country was built on slave labor—(but) it is a fact and you can’t get away from it.” says Pringle. “We have to understand our history to understand why there is an angst and ill-feeling when you start to think about enslavement.”

SWNS

74-year-old Anne Tinker, who is a direct descendant of the Middleton family, and has attended all three reunions, said, “At the first reunion we were all strangers and not quite comfortable with knowing how to express our past and our future. By the end of the next reunion, we were all friends.

“One of the things that is beneficial is we can talk to each other about race,” added Tinker. “We can acknowledge that slavery was evil, but also what we have in common and how we can move forward to make things better.”

Tinker has understandably conflicting emotions about her ancestor Arthur Middleton, an immensely wealthy slave owner, because he was also one of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

“I feel very proud that he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and these beautiful gardens and houses that he left behind,” she said.

“But what makes me sad is that the family’s contributions to US history would never have been possible without the contributions of African Americans who provided the labour, looked after the children, and shared their knowledge on how to grow rice. Slaves made the Middleton wealth possible.

“I think the Middleton Place Foundation has taken a very important leadership role in trying to improve communication and an exchange of ideas,” she concluded. “We are learning what we can do today to make it a better country and a better world.”

The next reunion is planned for 2021.

Rose Morton has written a book, “Our Family’s Keepers”, about her ancestors’ lives on the plantation. The story of slavery and its 21st century impact at Middleton Place was also the subject of the 2017 documentary Beyond The Fields.