By Melissa Lockers, Fast Company, February 21, 2019

By Melissa Lockers, Fast Company, February 21, 2019

In the world’s largest humanitarian warehouse, robots and humans are ready to dispatch virtually anything to anywhere, from dignity kits to a giant school-in-a-box.

In January, Milly Bobby Brown, UNICEF’s youngest Goodwill Ambassador, examines a school-in-a-box at its Copenhagen warehouse.

When the earthquake hit Nepal in 2015, a phone rang in a nondescript warehouse on the outskirts of Copenhagen. That’s where UNICEF’s largest supply hub sits filled with enough medicine, food, water, and material on hand to cover the immediate needs of at least 200,000 people, along with a robot-assisted skeleton crew of warehouse workers waiting to load them up and ship them out when the need arises.

Within 24 hours of the call, the supplies were being loaded; within 48 hours they were on a plane; and within 72 hours they are on the ground, making their way into the hands of the nearly 1 million children who desperately needed them.

“Supplies” understates it. That could mean essential rescue gear, or food and clean water supplies for victims of a hurricane or earthquake, or it could include items to address more long-term needs like malnutrition among people facing ongoing humanitarian crises: measles and polio vaccines in Libya, water drilling rigs and water purification tablets in Sudan, school-in-a-box kits filled with supplies to help children get back to the normalcy of school in a refugee camp in Bangladesh, or ready-to-use therapeutic foods bound for the crisis-ridden Lake Chad region.

Edgard Mounib Seikaly, a technical specialist for the supply division, says that when an emergency strikes, UNICEF workers start collecting data from people on the ground and working with partners to determine next steps.

“It’s always an emergency coordination between the country, Geneva, New York, and us, and the emergency response team that is there at the onset of any kind of an emergency,” he explains, referring to UNICEF’s headquarters. “As soon as they all get together, things start to happen, and things get decided.”

Soon after, the emergency supply list–basically a humanitarian packing list–is put together, and the warehouse jolts into action, pulling supplies and loading them onto a plane to ship out.

Inside the high bay in UNICEF’s global warehouse in Copenhagen, which handles 4 per cent of the charity’s total annual procurement. [Image: Ann Reinking Whitener / UNICEF]

Also in the warehouse is the largest item UNICEF produces, an inter-agency emergency healthcare kit they use in collaboration with Doctors Without Borders.

“It’s for 10,000 people,” says Seikaly, explaining that the container-sized kit includes everything from medicine to medical equipment to water sanitation supplies. “It’s basically a field hospital that goes into any kind of emergency.”

A GIANT LEGO SET FOR GOOD

The area known as the High Bay inside the world’s largest humanitarian warehouse is eight stories tall with yellow forklift-like robots zipping up, pulling out pallets of supplies, and bringing them down to the loading floor, where they are put on a track to be packed. When I point out that it looks a bit like a Lego set, Seikaly shrugs, “It is Denmark, after all.”

The High Bay’s robots run 24 hours a day, regardless of whether there’s an especially urgent situation (although, when you’re talking about the lives of children, almost every situation is urgent, even if earthquakes and man-made disasters tend to heighten the feeling). As the robots zip up and down in the High Bay and conveyor belts meander through the cavernous space, the result is a warehouse that looks similar to Amazon’s robot-assisted facility, albeit with a higher purpose.

“The High Bay is constantly looking to see what production is going to run the next day, so it starts pulling out pallets to prepare them,” explains Seikaly. The robot is trained to manage items with expiration dates–medication, chlorine tables, sanitation items, too. “The system knows how to move these things around in a fully automated way,” Edgar says. “It’s extremely impressive at peak time, dynamic and beautiful to watch.”

When an emergency does hit, the system kicks everything up a notch. Robots pull the supplies, while humans put together the kits, boxed supplies targeted to specific needs, whether emergency obstetric kits, personal hygiene, menstruation kits, cooking kits, school supplies, recreation kits, and what UNICEF calls dignity kits.

“They include things that would make a family living someplace feel comfortable and retain their dignity when they’re in a camp situation,” says Seikaly.

The warehouse, which was donated along with the nearby office space to UNICEF by the Government of Denmark in 1962, is filled with the items necessary to ensure that, like their slogan says, every child can have a childhood. That includes food and water and vaccines and medical supplies, of course, but also toys, crayons, art supplies, puppets for storytelling, math books, extra-tough soccer balls, and soap.

“The biggest lifesaver for us is soap,” says Seikaly. “It is the one product that basically can reduce infant mortality by a huge number.”

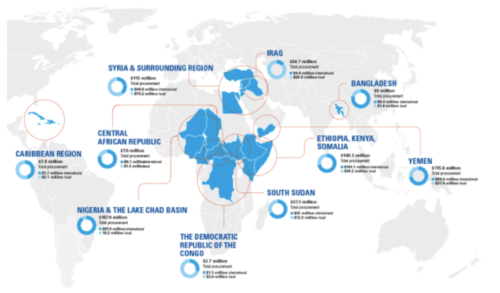

UNICEF’s largest deployments in 2018 [Image: courtesy of UNICEF]

As a bulk buyer, UNICEF uses its scale and buying power to cut deals with suppliers, to make the most of its financial resources. The organization is entirely funded by voluntary contributions from the public and the private sector, and does not receive funding from the UN. And it uses its buying power for good: Besides enforcing quality standards for its products, it has also managed to compel manufacturers to create more of the lifesaving ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) that it distributes to hungry children.

RUTF is a peanut-based product that doesn’t have to be mixed with water, meaning it’s less likely to be contaminated when served in communities that may not have access to clean water. The best-known version of RUTF is the evocatively named Plumpy’Nut, but there are other iterations, too. RUTF costs less than 50¢ per packet, according to UNICEF, and one case of 150 packets can treat one child suffering from severe acute malnutrition for two months, although treatment depends on the severity of the case. To say it’s an important tool in the doctors’ arsenal is an understatement–it’s one of the only tools available.

In 2000, manufacturers produced three tons of RUTF, but when supplies ran short and children’s lives were at stake, UNICEF stepped in to throw its weight around. By 2011, with over a dozen new suppliers pitching in, global production of RUTF reached 27,000 tons, most of which was headed toward UNICEF’s warehouse, ready to dole out when necessary.

UNICEF also uses its buying power to push for innovations, like new tools to diagnose pneumonia in children and more ergonomic and child-friendly school furniture (they buy millions of dollars of chairs and desks each year), or to encourage development of products like the SolarChill refrigerator, a solar-powered refrigerator that can protect vaccines from the heat in even the hottest corners of the world.

As it grows and develops its supplier network, the charity says it’s also working to make its purchasing more local, adding an economic element to their humanitarian missions in countries around the world. All of its purchases are meticulously tracked here and here for transparency purposes, and 89% of every dollar goes to the children. (You can donate here.)

Supplies leave UNICEF’s Copenhagen warehouse by cargo plane, bound for children and families who need them most. As the supply division loads the planes, teams of logisticians are on the ground trying to get as close as possible to the site of the emergency to figure out how to help.

“The team on the ground usually has 48 hours to think of how they’re going to bring supplies from point A to point B and then to point C and D,” Seikaly says, noting that UNICEF is frequently coordinating between different UN agencies and other nonprofit groups.

When the supplies arrive, UNICEF’s impressive and expansive logistics team usually has a distribution plan.

“If the infrastructure is available and you can land, that’s great,” says Seikaly. If the infrastructure is not there, though, UNICEF turns to airdrops, which is why many of the kits in the warehouse are designed to survive a drop from the sky.

“The school-in-a-box kit can withstand an airdrop of about 8 to 10 meters without any damage to anything that’s inside,” says Seikaly.

They’ve used convoys of trucks to carry supplies through a land-locked region and, to get supplies to the starving children in Yemen, they conscripted local fisherman in Djibouti to deliver supplies across the strait.

On a recent deployment to Chad as part of Norwegian’s Fill A Plane campaign, UNICEF staff and volunteers did just that, filling a brand-new Boeing 737-MAX with as many humanitarian supplies as possible: 2,000 water purifiers, 1,000 doses of antibiotics, 35,000 packs of rehydration salts, and more.

The mission delivered water purification kits and RUTF to malnutrition clinics in the capital N’djamena, as well as school-in-a-box supplies, dignity kits, and more to refugees living in camps after escaping Boko Haram and civil unrest in the Central African Republic and Sudan.

The situation in Chad is particularly dire, because few people are paying attention. For a decade, the region of 37 million people has been gripped by ongoing bouts of armed conflict and some of the world’s most severe food shortages, with 3.3 million people at “crisis” or “emergency” levels. According to UNICEF, displacement and fear of attacks have left more than 3.5 million children without access to education.

Last year the charity said it was only able to raise 35% of the $54.1 million it asked for, leaving many children without their needs met. But the warehouse is at work right now, buzzing with robots and the determination of people to carry out their mission, and do whatever is necessary to save the lives of children as quickly as possible.