What the SNC board may have known about the firm’s dealings in Libya — like the office safe with $10M cash

What the SNC board may have known about the firm’s dealings in Libya — like the office safe with $10M cash

High-paid former directors could face tough questions if SNC-Lavalin bribery trial goes ahead

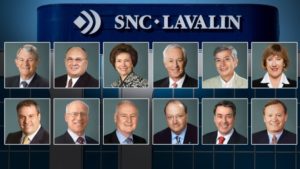

The SNC-Lavalin board in 2011. From top left: Ian A. Bourne, David Goldman, Patricia A. Hammick, Pierre H. Lessard, Edythe A. Parkinson-Marcoux and Lorna R. Marsden. From bottom left: Claude Mongeau, Gwyn Morgan, Michael D. Parker, Hugh D. Segal, Pierre Duhaime, Lawrence N. Stevenson. (SNC-Lavalin/CBC)

There’s no question that millions of dollars in bribes were paid to the Gadhafi regime in Libya to win lucrative contracts for SNC-Lavalin.

The former head of the company’s global construction arm admitted to bribery, corruption and money laundering in 2014. He pleaded guilty in a Swiss court.

But the Quebec-based engineering firm has long insisted that Riadh Ben Aïssa was acting alone and in secret.

“The Libyan bribes were disguised by Riadh Ben Aïssa as part of normal project costs,” former board chair Gwyn Morgan told CBC News in a recent email. “There was simply no means for board members to detect them.”

Ben Aïssa has a very different story to tell. He is back in Canada after having spent more than two years in prison in Switzerland.

He has turned on his former executives and board of directors and has been co-operating with police and prosecutors.

If called to testify at an SNC-Lavalin trial, he could expose who else in the senior ranks may have known about $47.7 million in bribes and $130 million in fraud tied to projects in Libya — crimes the RCMP alleges were committed by the company between 2001 and 2011.

SNC-Lavalin has been lobbying hard behind the scenes to secure what’s called a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) to avoid going to trial. The company, as well as its supporters in government, argue thousands of jobs are at risk if it is convicted and barred from bidding on federal contracts.

- WHO’S WHO | Learn more about the 2011 board of SNC

But a CBC News investigation reveals why 12 top directors who left the company years ago also have plenty at stake if the case goes to trial. SNC-Lavalin’s former board is an influential who’s who of the corporate elite that includes former senators, banking executives and members of the Order of Canada. They will all likely face close — and very public — scrutiny if called to testify about whether they knew of any corruption happening on their watch.

Former SNC executive vice-president Riadh Ben Aïssa, right, pleaded guilty in Switzerland in 2014 to paying bribes to Saadi Gadhafi, left, son of the late Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi, in order to land contracts for SNC-Lavalin. (Radio-Canada)

By piecing together public records, including past testimony, exhibits, depositions and separate civil suits involving the company, CBC News has uncovered a string of instances where those board members were allegedly told of financial irregularities — including a $10-million stash of cash kept in an office safe in Libya.

A court has not yet ruled on the credibility of most of the evidence and claims.

However, if the claims and allegations are true, it means the company, despite red flags, continued its lavish spending to win contracts from Libya’s Gadhafi regime.

Big bills

In 2008, SNC-Lavalin played host to Saadi Gadhafi. The playboy son of the Libyan dictator spent three months in Canada, visiting Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver in a trip arranged by Ben Aïssa.

Outside auditors raised concerns about the bills totalling $1.9 million.

RCMP forensic accountants have since scoured 44,000 pages of company records. At the 2017 preliminary hearing for bribery charges against an SNC-Lavalin financial controller, Stéphane Roy, investigators testified that they uncovered bills for private security and hospitality that included:

- $30,000 for escorts.

- $180,000 for a stay at the Hyatt Regency in Toronto.

- $193,501.81 for limousine rides.

- Cash advances of up to $15,000.

The CEO at the time, Jacques Lamarre, who himself travelled to Libya twice to meet dictator Moammar Gadhafi, says the runaway tab was submitted by the private security firm entrusted to oversee Saadi’s visit.

“Everybody was so mad. The board was mad. Everybody was really, really unhappy about that $2 million,” Lamarre, who also sat on the board, told CBC News.

“At the end of the day … what do we do? We did pay it. But we were very unhappy about that.”

Former SNC-Lavalin CEO Jacques Lamarre says he knew nothing about bribes and was betrayed by his former top construction executive. (Adrian Wyld/Canadian Press)

Regardless of whether it was a bribe or not, the board raised concerns in early 2009 when told about the size of the Gadhafi bill, according to Gilles Laramée, the chief financial officer at the time, in a deposition as part of a civil suit between SNC-Lavalin and former employees.

He said the board asked him to deliver a “serious warning” to Roy.

The safe

In May 2009, it appears the board learned of another possible red flag.

Stashed in a safe at the company’s headquarters in Libya was $10 million cash, according to Laramée.

The board demanded the company stop holding so much cash, he stated in the civil case, ordering that no more than $1 million be kept in the safe at any time.

CBC has reached out to the 12 people who sat on SNC-Lavalin’s board between 2001 and 2011 to ask what they knew about any bribery or improper payments by the company during that time.

“Absolutely nothing,” said Gwyn Morgan, the only board member to provide substantive answers. Most declined to comment or never responded.

Gwyn Morgan was board chair during SNC-Lavalin’s 2012 bribery scandal. He says the board was unaware of a top construction executive’s ‘cleverly disguised deeds.’ (Fred Thornhill/Reuters)

He says the board was completely in the dark about how Ben Aïssa was using company money and whether he was paying kickbacks to the Gadhafis.

“I have no reason to believe that other management members were aware of his cleverly disguised deeds either,” said Morgan, who served on the board for eight years. He was chair in 2012 when the bribery allegations first made headlines.

The board at the time comprised luminaries of the corporate world, including Sen. Hugh Segal, former senator and Liberal Party executive Lorna Marsden, four members of the Order of Canada, and heavyweights from the banking, energy and railways sectors.

Party for 50 Cent

Despite the board’s apparent concerns only months earlier, nothing stopped executives from hosting Saadi Gadhafi again in September 2009, when he attended the Toronto International Film Festival.

SNC-Lavalin again picked up the tab. It paid $430,767 for the much shorter visit that included the following receipts:

- $107,413 for a private party with rapper 50 Cent and 200 guests.

- $33,005.70 for limousine services.

- $200,000 for the Park Hyatt stay of 50 Cent and his entourage.

The RCMP alleges all the money spent on Gadhafi, a foreign official involved in awarding SNC-Lavalin contracts, amounted to bribery.

But the Roy case was dismissed in February due to delays getting to trial. That means a judge has never ruled on whether these payments were illegal or whether anyone else knew what was going on.

Former SNC-Lavalin vice-president Stéphane Roy leaves a courtroom in Montreal on Wednesday, Feb. 13, 2019. (Paul Chiasson/Canadian Press)

“The company, the CEO, the office of the president, the board of directors — they were aware of Saadi Gadhafi’s visits,” Ben Aïssa testified in the Roy preliminary hearing. “There were a whole series of prior authorizations for the visit.”

Former board member Gwyn Morgan denied Ben Aïssa’s claim in an email to CBC News.

“The hostings were arranged by Riadh Ben Aïssa without the board’s knowledge, like other regrettable things we now know he did.”

Former SNC-lavalin executive Riadh Ben Aïssa alleges the company bought Saadi Gadhafi this $38-million yacht. (Palmer Johnson)

Ben Aïssa also contends in the various proceedings that CEO Lamarre signed off on buying Saadi Gadhafi a $38-million yacht in 2007 to win a $450-million contract in Libya, and that Lamarre’s successor as CEO, Pierre Duhaime, even discussed buying Gadhafi a jet.

Lamarre denies the claim. He told CBC News he only read about the yacht in the newspaper after leaving the company and that it was all Ben Aïssa’s doing.

Between 2001 and 2011, SNC-Lavalin won contracts in Libya totalling at least $1.85 billion.

“These were contracts we got thanks to the influence, to the involvement of Saadi Gadhafi,” Ben Aïssa testified in 2017 in the Roy case.

“I didn’t do this on my own. The company pushed me to do it. I’m a company man. I did what the company asked me to do. Yes, it was criminal. I pleaded guilty.”

Is a member of the board of directors not going to ask the question, ‘How are we getting all of these contracts in Libya?’

– Patricia Adams, executive director of Probe International

The SNC-Lavalin case is the biggest corporate corruption proceeding in Canadian history, and raises questions about corporate governance and responsibility.

The firm’s former board members, with deep corporate experience, collectively received millions of dollars in compensation, and were responsible for overseeing one of the largest companies in the country.

“Is a member of the board of directors not going to ask the question, ‘How are we getting all of these contracts in Libya?’ I mean really!” said Patricia Adams, executive director of Probe International, a government and corporate watchdog group based in Toronto.

- Send tips to [email protected] and [email protected]

“What’s your role on the board if not to protect the corporation from acts of bribery and from doing things that are illegal?”

At least four members of the board at the time had MBAs. Pierre Lessard is a fellow of the Quebec Order of Professional Chartered Accountants. Claude Mongeau, who sat on the SNC-Lavalin board’s audit committee for 11 years, was named Canadian chief financial officer of the year in 2005 while at CN.

In October 2018, SNC-Lavalin, including the former board directors, settled a $110-million class action lawsuit by shareholders. The plaintiffs had claimed the company failed to disclose improper payments, prompting the company’s stock to tank after the bribery scandal was exposed.

No one admitted any wrongdoing.

Tens of millions in ‘improper payments’

Ben Aïssa claims he travelled to Libya in August 2011, after civil war had broken out, and successfully recouped $100 million owed to SNC-Lavalin for its work on construction projects. In civil suit documents, he claims he received a standing ovation from the board when he returned.

Soon after, the Gadhafi regime was toppled. Members of the family faced international sanctions, including a United Nations resolution that banned them from leaving the country.

Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, seen in this file photo from 2008, was killed by a mob during the country’s civil war in 2011. (Sergei Grits/Associated Press)

In February 2012, CBC broke the news that Roy was detained in Mexico as part of an alleged plot to smuggle Saadi Gadhafi out of Libya to a life in hiding.

That very day, the company hired law firm Stikeman Elliott to launch an independent review.

The findings sparked massive upheaval at the company. SNC-Lavalin announced the review had found breakdowns in its internal ethics protocols and millions in “improper payments” on projects in several countries.

SNC-Lavalin has undergone a major overhaul since 2012.

It is appealing once again to the Federal Court in a bid to force prosecutors to consider an out-of-court settlement. In court documents filed April 4, the company trumpets “the complete turn-over of SNC-Lavalin’s senior management and Board of Directors, since the events in question” as one of the reasons it should be granted a DPA.

But the documents reveal for the first time why prosecutors have denied SNC-Lavalin a DPA, stating the company doesn’t qualify for three reasons:

- The “nature and gravity” of the case.

- The “degree of involvement of senior officers of the organization.”

- The fact that SNC-Lavalin “did not self-report” the alleged crimes that are at the centre of the case.

A judge is expected to rule May 29 on whether the case will go to trial.